The Bishop Strachan School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of The Bishop Strachan School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

The mission of The Bishop Strachan School (BSS) is to provide an opportunity for each girl to understand who she is, know her place in the world, gain independence, build leadership skills, and find a voice in a multiplicity of voices. It’s a lot, to be sure, though throughout the century and a half of its life, BSS has demonstrated an unwavering ability to do exactly that.

The building, from the front, conjures long-standing tradition; from the back, it is cutting-edge modern. “That’s actually who we’ve always been,” says Dr. Angela Terpstra, Head of School, in light of the duality. “The school had an improbable beginning, and that improbability has continued all the way through.” She feels that the impression the front of the building might suggest—staid, old, traditional—“is actually deceiving because we are perhaps the biggest risk takers in girls’ education in this country. Whatever it is, [the approach] has just always been, ‘Well, let’s give it a go!’”

“We are that front,” says Dr. Terpstra about the façade of the school, “but we are much more than that front.” As illustration, she mentions the story of Dr. Anne Innis Dagg—“she’s one of our great graduates”—who is a biologist, author, and pioneer in animal behaviour. She arrived in Africa at 23, alone, to study the behaviour of giraffes in the wild, becoming the first person to do this kind of study of any African animal population (four years before Dr. Jane Goodall, and seven before Dr. Dian Fossey). Dr. Dagg was also the subject of the 2018 documentary The Woman Who Loves Giraffes.

“The other part of her story,” says Dr. Terpstra, “is that she was refused tenure at [The University of] Guelph, even though she had a CV bigger than all the men applying put together. And so in a way that’s us, too: forging forward into the future and taking a principled stand, taking an interest and a deep love in something, and going forward with it, realizing that you’re going to come up against the Canadian establishment, or [other obstacles].”

The world has changed since BSS was founded, and perhaps people have, too. The professions available to women today are greater, vaster, and different than those of even 50 years ago, let alone a century or more. The post-secondary options, too, have multiplied, as has girls’ access to them. Throughout, BSS has worked to address all of those changes, while maintaining an eye on the things that will never change—namely, a need for girls to have the confidence to raise their voices and deploy their talents in the world, navigating between achievement and challenge.

The list of alumnae includes many who have made a positive impact on Canadian life. One of them, social activist and author Emily Murphy, depicted in a monument on Parliament Hill, has appeared on the $50 bill and is officially recognized as a Person of National Historic Significance. Others have defined aspects of the local and national discourse, including television host and journalist Valerie Pringle and pioneering computer scientist Beatrice Worsley.

Jennifer Lee is an alumna and, like many others, she maintains an active role in student life, fueled by her sense of what BSS can do and a desire to continue taking part within it. Among other things, she takes girls into the business and teaching environments that she works within as part of her professional life, including workshops at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, where Ms. Lee completed her MBA. “I took them into a series of meetings—about startups and scaling nascent technology—and put them in rooms with some of the leading entrepreneurs in Canada, as well as some from Silicon Valley. And I was so impressed at how articulate the girls are and the types of questions that they ask, how they take that back to school, and how it informs their work.”

Ms. Lee feels that’s a product of the school’s approach. ‘The girls that come out are so incredibly polished. I watched them do the pitches at the end of the Blockchain Hackathon. I was on the judging panel and I honestly think the girls presented—with their presentation style, their slides, and their demos—at a higher caliber than some of my MBA counterparts at Rotman. I was really, really impressed.”

The girls’ work would probably surprise and impress even BSS’s original founders. Certainly blockchain hackathons weren’t on their radar, but the idea of getting up, speaking out, and taking a place at the table certainly were. Anne Thomson, principal of the school in the 1870s, once addressed the students saying: “Remember girls, you are not going home to be selfish butterflies of fashion. The Bishop Strachan School has been endeavoring to fit you to become useful and courageous women. I believe you will yet see our universities open to women. Work out your freedom, girls! Knowledge is now no more a fountain seal’d; drink deep!” If she were able to attend today, Thomson would see that her directive is very much in evidence. There’s a notable dearth of butterflies, and a wealth of usefulness and courage.

That the program stretches and grows student interest into areas they may not have considered is a principal reason families turned to the school a century ago, and why they continue to do so now. “I really appreciated that BSS could support my interest in doing OAC biology as well as advanced placement writers’ craft,” says Ms. Lee. “That I could really get the whole breadth of my interest … and that faculty supported my diversity of interest.” She says their advice to her was “don’t feel pressure to build skills in your undergrad that are going to be applicable to finding a job. Remember to learn to think about the world, and learn how to write, and learn how to analyze. Those are the skills that will carry you forward. … Do the things that you like, think broadly about the world, learn to be analytical—the rest of it will come.” It certainly has for Ms. Lee, and she attributes that directly to her time at BSS.

Key words for The Bishop Strachan School: Identity. Challenge. Possibility.

Basics

The Bishop Strachan School (BSS) is a girls’ independent boarding/day school located in Toronto, Ontario. It offers a liberal arts education and includes a Junior School, comprising JK through Grade 6; a Middle School, comprising Grades 7 through 8; and a Senior School, comprising Grades 9 through 12.

The façade dates to 1913 and was created by the same architects who designed Hart House, College Park, and the Royal York Hotel. It was designed with tradition in mind, that of the great UK independent schools, such as Eton College, Harrow School, and Winchester College. Set back from the street in one of the leafiest, most desirable, most celebrated communities in Toronto, that sense of tradition is what you experience first. The school recently celebrated its 150th anniversary, making it one of the oldest schools in Canada. It was founded in 1867, the same year as Confederation, by Reverend John Langtry in order to provide a quality, Anglican education to his four daughters. His intention, as he outlined in the school’s first prospectus, was to provide a first-class education with an “emphasis on subjects that would develop understanding, strengthen the judgement, and refine the taste.” The school was open to all, with the one proviso that the students were willing to conform to its regulations. Fair enough.

On opening, it became the first Anglican girls’ school in Toronto and one of the first in the Commonwealth. From day one, it was charting new territory in education and in the national culture. Compared to boys’ schools of the time, girls’ schools were created to prepare their students for a very different set of roles, including those within private and philanthropic life, and within the caring professions, such as nursing and teaching. The BSS prospectus noted that the program was created to educate women with an eye to “the serious duties of life as members or heads of families.”

The reality is that BSS did considerably more for its students than that, and it played a larger role in Canadian life as well. It quickly became an example of forward thinking, particularly in terms of women’s rights. It’s not a quirk of fate that Emily Murphy was educated here. She went on to become an indefatigable activist, the first female judge in the British Empire, and one of The Famous Five who helped bring the Persons Case forward, allowing women to participate more fully in government. It was during her time in BSS that she found both her voice and her audience.

Beginning with Anne Thomson, who became principal in 1872, the school was led by a series of forthright women who had lived at the boundaries of social and intellectual life, an experience that they brought to their role as educators. Thomson’s views were revolutionary for the time, and they found a welcome home at BSS. She and those who followed would define the life of the school as challenging and progressive, a place where girls and women would continue to work out their freedom and “drink deep,” just as Thomson hoped they might.

After becoming principal in 1899, Helen Acres instituted a program of physical education and inaugurated a sports day, both of which included sports that were considered “unladylike” at the time: cricket, basketball, and ice hockey. That resonated beyond the walls of the school—it was a conspicuous political move—but most importantly, it resonated with the students themselves. They were being encouraged, if quietly, not simply to accept the status quo, but rather to become leaders effecting real change in the world.

In 1911, Harriet Walsh became the first headmistress at BSS—gone were the days of the “lady principals”—and she strenuously continued the work of those who had come before. She began by travelling to schools in England and the US in order to find strategies and techniques to modernize the school’s curriculum. Back at the school, she instituted a program of financial assistance, the first of its kind in Canada, offering bursaries and scholarships in order to broaden the student base. She wanted students who were academically able and who could add social and academic diversity to the student body. The kind that could really benefit from what the school had to offer, not simply the daughter of the wealthy. She wanted to create a community with a reputation of achievement, not privilege. During her tenure, the school sent more students to university than ever before.

It was through that kind of leadership that girls’ schools departed most significantly from what was happening elsewhere. While all-boys schools could be brutal in the pursuit of conformity, the girls’ institutions were quietly empowering girls to do more, and to demand more of society as well as themselves. The women who taught here were modern and accomplished, and they imparted the values of education. They led by example, providing a window onto a world of possibility. Though times have changed, the dedication at BSS to increasing opportunities for women continues—most recently in the areas of science and technology—all while empowering them to trust their instincts. “This place had provided such a sense of security that it helped launch me,” says journalist and alumna Valerie Pringle. “I couldn’t have been in a better place in those years in my life.”

The geography of the school is a lesson in the efficient use of space. Today, while occupying the same parcel of land it did when it was founded, it accommodates considerably more programs and students than it has at any point it its life. The property is large for the neighbourhood that it sits within, though it isn’t sprawling by any standard. Some of the outdoor sports facilities sit on top of the parking garage, though the architecture is so discreet and sympathetic that not everyone is entirely cognizant of it. The ground-level parking area, too, is nicely tucked away, and doesn’t dominate the property. Given the challenges of space, there’s a surprising amount of green and a welcome amount of elbow room. The Junior School playgrounds are there, as well, and are spacious and well appointed.

The school community refers to the recent development as the new building, though it’s not separate. The bulk of the instructional activity takes place within what is, in effect, a single building. “There’s a practicality to that,” says Ms. Catherine Hant, Principal of the Junior School. “We feel strongly that the learning of children, no matter what the age, [be] transparent to the other kids in the building, and the educators and leaders in the school as well.”

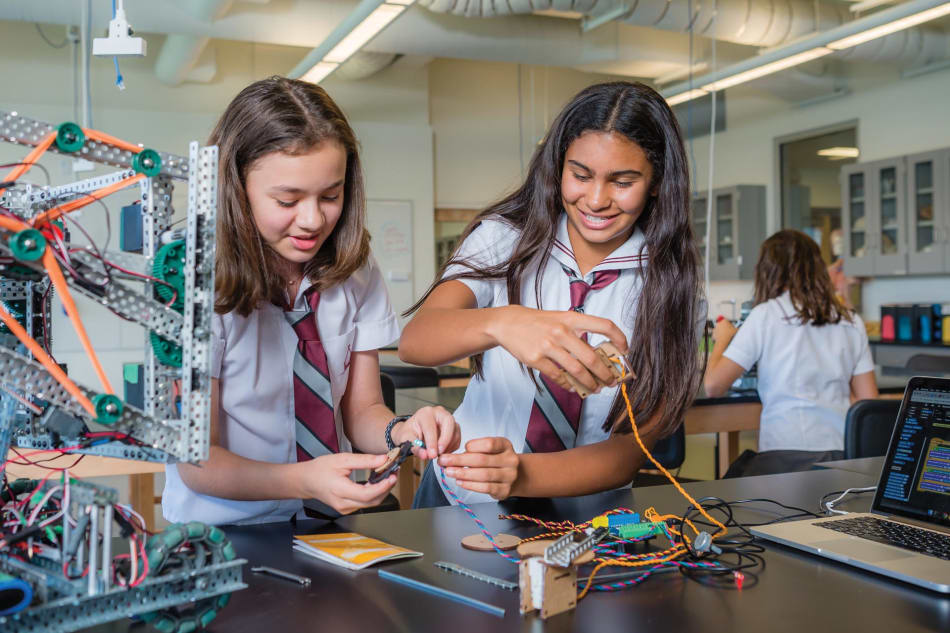

When asked where one would take a visitor who had time only to see one thing a member of the student recruiting team, answered the Design Technology Lab, a cornerstone of the recent capital and development campaign. “Because it’s not only about design/tech. It’s where the girls will take geometry, for example, to the creation of a snowflake, and then create the snowflake in the 3D printer based on the mathematical formula. And then, understanding the biology and the science side of it, to investigate how a snowflake absorbs bacteria, pollution. That’s what I would show you.”

BSS opened its Design Tech Lab in 2017, something that underscores the dedication to drawing connections between disciplines. It’s a concept borrowed from what Jonas Salk created at what is now the Salk Institute at MIT. Salk called it a “crucible of creativity,” and an expression of his belief that “most of the exciting work in science occurs at the boundaries between disciplines.” Salk wanted to create an environment in which scientists could “explore the wider implications of their discoveries for the future of humanity.” Through the Design Tech Lab, BSS put those ideas into practice. At BSS, there’s an understanding that bringing disciplines together, allowing them to intersect naturally by virtue of proximity, will empower the students, delivering the skills they’ll need when they enter post-secondary and professional life.

Leadership

“These girls need teachers who will push them, perhaps, into things they would never do,” says Dr. Terpstra, who has been Head of School since 2018. “They need teachers they trust.” That reciprocal relationship is a cornerstone of the programs of her approach. “For many of us, our high school years were very limiting, because you were on a track just to get to university.” Dr. Terpstra intends that BSS offer something more than simply that transaction, namely that the school will deliver students to university, but that they will also explore their interests, grow as people, and find their place in the world prior to arriving there. The students call her Dr. T. “I’ll answer to ‘hey you’ too though,” she says with a laugh. And no doubt she would. She’s available to the students, and entirely approachable. That’s rightly important to her. “One of the things that strikes me as interesting is that we are incredibly proud of the academic development, and the futures of our students. And we are a very caring community. Though somehow people think that if you’re caring, you must be academically not as strong. But I would challenge them on that every moment. I think that we are a caring community with an incredibly strong academic prowess.”

She believes that the caring community that the school provides is responsible for future success, and her passion rises when discussing that aspect of the school’s offering. “In the business world today, that’s what employers are looking for: well-rounded, strong communication skills, being adept at numeracy, being able to ask questions, understanding the dynamics of personal situations. Those are key things, as well as knowing how to get things done. If you look at the qualifications now for NSERC and SSHRC grants [to support post-graduate research], they’re looking for: Are you interdisciplinary? What’s your communication plan? Are you working with younger students? All those kinds of things that we are building into our program.”

Dr. Terpstra came to BSS in 2005 from a post-secondary background, having taught English at the university level for 13 years. It’s not a typical career trajectory. “I think I’ve followed my nose more than having been strategic,” she says. “I have this little maxim that my kids follow: sometimes you need to do things that will make more of you. What will make more of you? And I think that’s an interesting way to think about challenges. You think ‘will this make more of me?’”

It’s an interesting tension within the school culture—that between strategy and instinct—and one that animates it to some degree. Again, it’s evident even in the structure and appointments throughout the school. The foyer just inside the main entry is lined with oak panels displaying award winners dating back nearly a century. It’s charming, if a bit overbearing, though the sense that you’re in an environment of long-standing achievement is clear. Moving beyond the foyer and into the instructional spaces, the school’s age isn’t apparent. All the key spaces are filled with natural light, using glass walls that create a porous interface between them, with sightlines to the work within the classrooms. Where the divisions between programs were once stark—the music room was once on one floor, and the art and science labs on others—all are now intentionally cheek by jowl to allow for significant, regular cross-curricular interaction. “You’re not confined to a little box,” says one student, “but can see how your work connects with other things.”

“This world, to me, is a vocation,” says Dr. Terpstra. She wants to provide the students an introduction into seeing the world in that way. “What we have to do is use all the tremendous resources that we have around us to help them be their best people. To draw attention to things that we think, in this world, at this particular time and place, are important for them to know about. And we can do all sorts of things … we need them to be good people. Especially when the adolescent impetus is sometimes to just be inward. So, it’s always about getting them involved in things bigger than themselves, having them meet people who are interesting and who are different than themselves.”

Academics

All of the recent development, in particular, reflects a desire to create a classroom experience that is progressive, forward thinking, and providing a basis in the kind of collaborative work that students will engage in during their post-secondary studies and beyond. Dr. Terpstra and others use the term “well-rounded,” though they invariably are quick to qualify it. Across the faculty, well-rounded is understood to mean that a student is scientifically literate, mathematically literate, reads well, is prone to engage with others around shared tasks, and is aware of nuance in media.

It’s a liberal arts approach, though in a decidedly 21s-century version, or what Dr. Terpstra calls “liberal arts–plus.” There is an equal emphasis on the classic areas of academic interest, as well as contemporary ones, such as coding and financial literacy. The latter is a skill that is embedded into relevant courses beginning in Grade 10, leading to, among other things, a financial securities course in Grade 12. The financial courses address not only personal finance, but world markets and securities, and how those kinds of things have an effect on geopolitics. “It’s applying financial securities at a macro level to world issues,” says Dr. Terpstra. ”So it’s pretty cool.” She’s right. It is.

There’s an overt desire to ensure that there are real-world applications, a phrase that Dr. Terpstra admits can be overused. “It has to be something not just added on, but deeply embedded from the beginning of the project.” That includes bringing in alternate voices, and finding creative ways to drive engagement with the core curriculum. In English courses, students read traditional texts paired with contemporary ones, something Dr. Terpstra refers to as “contrapuntal texts.” Jane Austen, for example, may be paired with Jeanette Winterson, with students asked to isolate the female voice in each and consider how they differ and resonate with one another. “It’s a way that you can teach the canon, but then give it some interesting perspective.” It’s a more substantive way of interacting with the texts. Rather than students simply talking about their reactions to them—the “critical thinking,” I-liked-this-but-not-that school of English instruction—they engage with the texts in a meatier way, building arguments using the tools that the text provides. The approach also pushes them to consider the historical, social, and cultural contexts for the work in a more meaningful, active way.

“A lot of people talk about ‘critical thinking’ now,” says

Dr. Terpstra, “and I’m not sure that critical thinking has been a success. Because what I’d really like to see is students with the confidence and knowledge to argue with each other.” The methods and instructional environments of the school have been designed with that in mind. “Part of the critical thinking has been ‘well, we have to be nice to each other, and we have to agree with each other.’ And also, the other thing that’s happened is students don’t always feel safe to argue because they think it might be detrimental to their marks. And we’ve got to get them away from that and really understand that what’s good for you, in terms of your whole life education, is to be able to really engage in an argument.”

And how about writing well? “Yes!” says Dr. Terpstra, “That’s a really important skill as well. To be able to think, read, write well. I really think it’s a powerful thing to help a young woman find her voice, but I do think she needs to be able to use it—when to temper, and to understand the nuances, when to speak boldly, speak quietly—in moderated ways.”

That’s typical of the interactions we had with faculty and administration throughout the school. These aren’t people that revel in the past. Rather, there’s a palpable sense of momentum among the administrators and faculty—they are forward looking, keen to innovate with an eye to doing better, and continually adapting in order to meet present needs.

“I do think the standard and the expectations are higher [at BSS],” says parent Liz Pullos, in comparison to a private school her children attended in Australia prior to relocating to Toronto. “They sent home a reading list … issues to do with feminism, self-awareness, gender identity, and everything on the list covered those topics,” which she feels wouldn’t have been foregrounded in the same way at other schools. “I’m really delighted with the school covering those topics, as well as growing an awareness of community responsibility.”

“It’s constantly changing from when I started here,” says Ms. Rita Gravina, Head, Humanities and Social Sciences Department, citing the programming, opportunities, and initiatives. A notable example was in 1999, when BSS became the first school in the country to incorporate laptops into the classroom. “That shifted everything in terms of how we teach and how students learn. … and that’s what I mean when I say there are shifts along the way. They’re needed, and I’m sure there will be others as we move forward. But one of the things that has stayed the same is this idea of an inquiry-based approach. If there’s been a constant, that’s been the constant. Having the students dig in deep, having them engage in real-life learning. Having students go out and understand where we’re at today and trace it back to our own roots.”

The Reggio Emilia approach is applied in the Junior School, though it is emblematic of what happens in the upper grades as well. It was adopted because it complements current trends in secondary and post-secondary education and the workplace. The values of reciprocity, transparency, collaboration and knowledge-building are in harmony with the employability skills valued by the Conference Board of Canada, such as participating in projects and tasks by contributing expertise to a team, ability to communicate well in a variety of ways, and being able to think and solve problems in many different spheres. At all levels, there’s an overt intention to begin from where the students are, and to build on their interests and aptitudes. They’re not thought of as empty vessels waiting to be filled with whatever we think is useful, but instead approached as what they are: people who have their own views, opinions, ideas, knowledge, interests and passions.

The progress into conceptualized thinking is intentionally rapid, and based in an inquiry model through the middle and upper grades. There’s an element of co-writing, or co-constructing the content of the curriculum with the students. The hope is that they will approach the content through an authentic and genuine interest, and the academic program is designed with that goal in mind. The feeling is that it’s empowering, while also granting access to higher-order skills, and particularly those required for success at university.

There is a longer course syllabus than you’d typically see in a school of this size, the intention being to grant a wider range of opportunities for enrichment and to allow students to develop their passions while, at the same time, discovering new ones. All courses are developed on the basis of the Ontario provincial curriculum and grow out, often considerably, from that point. “We start with the Ontario expectations as the foundation, and we enrich and supercharge the delivery,” says Mr. Brendan Lea, Principal, Senior School. He says that there is a consistent emphasis on making interdisciplinary connections, often facilitated by reaching out to experts and experiences outside the school walls. “That means that some of our courses are more traditional, with essays and pen-and-paper testing. But we also have a whole world of activities and assessments and evaluations that go beyond that.” That could include seeking connections or information from beyond the classroom, or presenting to groups outside the school.

While the shorthand for the delivery of the curriculum is ‘inquiry-based,’ Mr. Lea is quick to note that, often, the approach is only vaguely understood, or understood in a very two-dimensional way. “There are different pedagogies that align with inquiry-based learning. … And so, inquiry-based learning isn’t all day, every day, [because with that method] the students are wandering through, looking for answers they may or may not find.” As such, there is an abiding belief that not all eggs need be placed in one curricular basket, as it were, but rather that deliveries and approaches should be chosen to suit the material and the students’ needs.

“In our math program, there’s a lot of problem-based learning,” says Dr. Terpstra, “where students will look at problems and solve those in connection to the real world. [But, ultimately] the teachers know what the students have to learn, and they know what the Ontario requirements are.” Like Mr. Lea, Dr. Terpstra is often at pains to be clear what the school intends by an inquiry-based approach, in part due to an awareness of what many, often incorrectly, assume that it is. She argues that, while there might be periods of time where activities are more open ended—driven either by student questions or questions posed by the instructor—they are balanced by a clear structure and program of assessment.

“What are the pedagogies that we can use?” asks Mr. Lea. “It can’t be a one-size-fits-all.” That’s one reason why the International Baccalaureate (IB) Programme, for example, hasn’t been adopted and—so long as he is at the helm of curricular development—won’t be. “The IB diploma program is narrower. And we love the fact that we’ve got gender studies, entrepreneurial studies, and those kinds of things,” which wouldn’t be possible under the IB umbrella. “The enrichment that is provided, say, through the higher-level Advanced Placement (AP) courses is great for students who are thinking of going to the United States or the UK” for post-secondary studies, he says.

The school’s approach to developing its own curriculum seems to be working just fine for many BSS parents. “I’m moved to tears on a regular basis based on what they’re teaching our girls,” says parent Michelle Pollock. “We were there for maybe two months and we had a meeting with the teacher. She knew our daughter better than [teachers over] three years at her previous school.”

The academic environment

“We have a lot of freedom, in terms of best practice,” says Ms. Genny Lee, Head of Science. “I remember one year they sent us all, the entire science department, to High Tech High in San Diego just to learn about best practices.”

In another instance, faculty went to Bard College, a private liberal arts college in New York State. They engaged in an exchange, with Bard faculty also coming to BSS, and the interaction led to the development of a writing/thinking institute. The approach is very much “where can we be learning, and what can we take?” Similarly, the Junior School has undertaken a pilot project with Ryerson University with respect to zone learning, which focuses on co-curricular opportunities for their students to develop entrepreneurial skills.

“We’ve invested a lot in professional learning,” says Ms. Hant, “and we’ve created this culture of learning together. We talk a lot about the environment as the ‘third teacher,’ and part of that is the role the teacher plays within that learning environment.” That includes creating experiences that ensure engagement, foster curiosity, and expose students to a wide variety of stimuli. Ms. Hant adds that it’s also about “shaking it up a little bit. I’m a big believer in not following routines all the time, because that’s life. So, being able to shift kids on any given day and scaffolding how they manage in those situations—I think that’s important. Those are the transferrable skills.”

There are some cross-over teachers that teach in more than one of the divisions, though they are limited to specialty areas. Beyond that, instructors are dedicated to a specific school. Nevertheless, as Ms. Hant notes, the interactions between them are many and frequent. Within the schools, however, teachers move between grades every three or four years. The intention is to keep things fresh, to model the importance of change, and to broaden teachers’ understanding of the scope and sequencing across the grades. “And, also, it’s just good to get out of your comfort zones and try something new,” says Ms. Hant. “They’re not on auto-pilot.”

“I was working on a project that I’m doing now, and I found a message from my mother where she said, ‘The teacher said that she sees so much potential in you, but she thinks you’re too comfortable.’ I remember reading that in Grade 9 … and now … I look back and I see what she was saying. … I did make a shift in my attitude and ethic, I guess, and I’ve seen it carry on into Grade 11. And one of the comments she made on my report card was, ‘[This student] always pushes herself past boundaries.’ And it’s funny to compare what she said. Even though it made me kind of think in Grade 9, her comment really pushed me, I guess.”

—Grade 11 student

There are leadership opportunities for older students to work with younger ones, most often around specific events or activities. As at any private school, leadership is a buzzword, though staff are careful to make sure that students understand that leading isn’t limited to standing at the front of the room. The intention is to allow students to discover what matters to them, and then providing opportunities to translate that interest into leadership. That said, leadership is rightly seen as a broad continuum of involvement, and not limited to planting flags or being first up the hill.

There is care to ensure that students grow into an understanding that leadership is both more varied and more nuanced than the stereotype. “I don’t want to be a leader through academics, or the things I know,” said one student, “but more through the attitude I give off. I want to be a leader that inspires other people to be positive and to be kind to others. It’s more about the character traits; they’re the most important.”

Instructors, for their part, lead by example. “Rather than telling them to do something,” says a student of a favourite teacher, “she teaches them to do something.” It’s a fine distinction, but for the others nodding in the room, a clearly meaningful one. It’s the other side of the coin: while teachers talk about a reciprocal learning environment, it’s confirmed by the students that they do indeed feel involved in the process of instruction. “She’s really supportive, but you have to stay on task.”

The faculty work closely around scope and sequencing to ensure that the Junior, Middle, and Senior Schools don’t exist in vacuums, but function as a consistent, symbiotic whole. Says Ms. Hant, “If you’re a child who is here potentially for 14 years, we want to know your trajectory, and not assuming that just because they move from one grade to the next that that’s going to be smooth.” That includes attention to academics as well as the social and emotional transitions. “From a teacher’s perspective, there’s an accountability piece. Because we’re all under one roof, how my kids do in Grade 6 impacts you as a Grade 7 teacher, because you’re inheriting my kids. We’re having lunch together, we’re doing curriculum planning together—there is that sense that we’re all in this together and we have to be talking to one another.”

Faculty have transition meetings at the end of each year, both within the schools and as students move between them. “We develop relationships with these kids and with their families. And the other aspect of this is that it’s a long-term relationship, and the continuity of that is important.”

“Female empowerment is always there. There’s never a doubt that you can’t do something. Anything you want to do, you can do it.”

—Grade 10 student

The Middle School program, in many ways, prepares the groundwork for what’s happening in the upper grades, including the connections to real-world experience. Mr. Ian Rutherford, the Principal of the Middle School, brings a wealth of experience and an infectious spirit. As in the Upper School, he’s keen to have the students working, hands-on, and in collaboration, with real world problems. A recent project titled “Legacy” had girls working with primary documents held within the school’s archive, researching and ultimately presenting aspects of the school’s political and social history. The intention was to learn about the past, says Mr. Rutherford, while also learning about the limits of the sources themselves, and the process of historical investigation. “It was about finding what’s here, what’s not here,” and relating it to the present day. The culmination was a two-hour immersive play, where girls interpreted moments in the history of BSS while positioned throughout the school, with the audience moving through the various stations.

That the girls had access to real documents—photos, letters, yearbooks, even hand-written dance cards—was, for some, itself somewhat electrifying. The project accessed a range of skills, including writing, interpretation, and presentation. And, it ultimately was tied directly to the girls’ own experiences. “So a lot of it was then coming up with the questions we posed at the beginning and using provocations around how we understand legacy. What is our legacy? What does it mean to have a legacy? Is it a verb or a noun? They’re playing a lot with that, and bringing it back to what it means for our own community. Who are we as a nation? What is our legacy as a country? And what is the legacy of the school in relation to Canada as well? Was the school reflective of its time, or was it ahead of its time? And then to think about themselves in that way: how am I different? What do we do for fun, compared to what they did for fun in the past?”

The Legacy Project is as good an example of inquiry-based learning as we’ve seen, and indicative of something that Mr. Rutherford seems particularly adept at bringing to bear throughout the Middle School program. They are big ideas, to be sure, but they are presented in age-appropriate ways, with lots of time given to develop an approach to them.

In another example, students were challenged to think about the feral cat population in Toronto. “The teacher introduced the idea that there’s a lot of feral cats in the city, and they suffer because people feed them because there’s nowhere to house them. So the project was to work with an organization to build the warmest possible box, a house for the cat.” They investigated material properties—why is Styrofoam better than paper, say—and then designed and built examples in the makerspace. They created 12 boxes, put them out into the world, and set cameras on them to see how cats liked the homes.

“The project has to be engaging,” says Mr. Rutherford, and clearly, all the examples we saw were. He showed us another, where students toured areas of the city, then imagined and built maquettes of potential buildings that could be created to provide housing, recreation, and the essentials of life. The strength of the program begins with that kind of engagement with each other and their world, though the curricular foundations are clear, including the essentials of writing, reading, processing, creative thinking, and presentation.

An interdisciplinary approach

“There are a lot of connections that can be made between disciplines,” says Ms. Gravina. “Even though they’re very distinct disciplines, I think the students are seeing how different courses connect with others. So [they see that] this might be a science issue, but it’s also a justice issue, and it’s also an equity issue. Being able to see the connections is another whole piece that I think the students benefit from.”

Mr. Andrew McCleod, a biology and chemistry teacher in the Senior School, says, “I think what can risk becoming overwhelming is when you have a lot of information that is disparate,” which is one of the reasons for the dedication to finding and promoting the interconnectedness between disciplines. “Eighty percent of our students who are taking biology are also taking chemistry, so the level of interconnectedness we can foster between those courses helps reinforce thermochemistry from respiration in biology. A lot of our students who take gender studies also take Grade 11 biology, and within that course we look at the science of sex versus the social aspect of gender. So we’ve done crossover the last few years with the gender studies classes to emphasize that and work on that connectedness. It gives a sense of continuity to the students and helps build connections between seemingly disparate concepts.”

The spaces add to the diversity of the students’ academic experience—from a university-style lecture hall, to Harkness rooms and cross-disciplinary labs. Classrooms include whiteboards and smartboards on the surrounding walls. iPads and laptops are used from Grade 7 up. Some of the classrooms have old-style blackboards, which are in place less because they haven’t been removed, and more because both teachers and students seem to like the variety they lend to the range of interactive display. “They’re just a really good complement,” says one student, “and we usually have access to both.” There are study spaces throughout the building, from the Learning Commons to less formalized spaces. “You can usually find me hiding in a corner somewhere, just getting work done,” says a student. “There are tons of little nooks, so if you want to isolate yourself, you can, but there are lots of collaborative spaces as well.”

Student population

While there isn’t a typical student, girls arrive with a healthy curiosity and are able to take pleasure in learning, and learning about learning. While it’s understood that everyone grows and learns at a different rate, the work is challenging and the level high. A desire to try new things, and to revel in new experiences, is a plus, as is an ability to thrive in collaborative environments.

At an annual population of 900 or so students, the school is on the larger side. That said, given the divisions between the Junior and Middle years, the feel is of a smaller institution. The atmosphere is personal and close-knit, and students are known to faculty.

There are 12 houses, named after prominent people within the school’s history, and every student is assigned to one: Pyper, Acres, Dupont, Grier, Griffith, Lamont, Langtry, Macnaughton, Marling, Nation, Rosseter, and Walsh. The houses grant a sense of belonging and are the basis for in-school competition and spirit events. Less obvious, but equally important, houses provide a frontline to the wellness programs of the school.

Boarding begins with Grade 8, and there are 75 girls from 15 different countries that live on campus. “We try to run it as close to a home as we can,” says Ms. Katherine Radcliffe, Assistant Dean, Boarding. Each boarder is assigned to a ‘family,’ the term used to describe a group of 15 to 20 girls that are from all of the grades, giving each a chance to get to know people outside of their grade. Six families make up a house, and the houses compete throughout the school year, accumulating points for activities ranging from physical fitness to participation in spirit events.

“Coming into exams, we wanted a little stress buster, so we have hands-on exotics”—as in exotic animals. “They brought a baby kangaroo and chinchillas,” says Ms. Radcliffe. The girls sign up for that and a range of other activities, from the expected (shopping, trips to local museums) to the impressively creative.

Boarding is facilitated by six staff members, two boarding coordinators, and four boarding advisors. Day girls are allowed to be in the dorm, though only boarding students have an access key. “Every evening there is family duty,” says Ms. Radcliffe. Looking into a fridge in a shared kitchen, she laughs, “and one of them is to clean out the fridge!” (The fridges actually looked pretty good.) Beyond that, housekeeping takes care of all. The duty roster, perhaps more than anything, is both a way of augmenting the girls’ sense of ownership and stewardship of the environment and, at the same time, keeping things in check.

Student life

The chapel is an important part of the school culture, and it’s as beautiful as it is formal. The same is perhaps true of the uniforms, particularly the ties, Oxfords, and jackets of the number one dress. (We asked a student if she likes the uniforms. She responded: “Well, I like that it’s not a plaid skirt.”) Members of the graduating class wear white jackets that include black piping. All of it can seem impressively old school, yet, once you get past the initial gestalt, the girls are clearly comfortable in the setting and the clothes.

“It’s a very comfortable space,” says a student of the chapel, and the sentiment is clearly shared. When asked about the carving and motto on the altar—In Cruce Vinco (“In the cross I conquer”)—our guide is quick to note that she’s not personally observant. The fact that she says that so readily is illustrative of the place of religion in the school: it’s part of the story, but not central to it. And, in any case, all are welcomed, and feel welcome. “I feel like everyone here just wants to help each other,” says one of the student guides.

Chapel offers quiet and reflective time and is more secular than many would expect—“it’s not preachy,” offered one student—and it provides a cornerstone of the school community. Says alumna Ms. Lee: “When we sang hymns, or when the Christmas trees went up in the chapel, everyone loved it because it was a symbol of our community, rather than overtly celebrating one choice over the other. And you could appreciate it for the non-religious associations as well. Like, the tree smelled amazing and looked beautiful in the space that we were in every day. And people could separate the elements a bit, and just look at it from a more macro perspective. It was about community above and beyond anything else, and everyone felt comfortable within our community.”

Chapel and assemblies are conducted by division, with Junior, Middle, and Senior Schools meeting on their own. Chapel is led by the school chaplain in, well, the chapel. “It’s done in less of a ‘rah-rah’ way,” says Ms. Hant of the comparison between assembly and chapel, “and more of a formal gathering where students know they are going to talk about something and reflect on it.”

The students are very attuned to issues of social justice, and that interest is developed through courses that focus on gender studies and women’s rights. That sense of the culture, for some, augments a sense of comfort. They see this as a different kind of space, one that is both more understanding and more forgiving than others they have moved through in their lives.

Athletics

“I’m a BSS Old Girl,” says Athletic Director Ms. Jameson, “and athletics was, and still is, a big part of who I am.” She adds that “so much learning happens on a sports team, and you can’t underestimate the benefits of camaraderie. The sense of trust, support, and friendship among team athletes runs deep and provides the security and acceptance girls need to be their best.”

The competitive offerings are significant, varied, and successful. Teams compete in the Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations (OFSAA), the Conference of Independent Schools of Ontario Athletic Association (CISAA), and Canadian Accredited Independent Schools (CAIS). Prior to Grade 7, there is a no-cut policy. While the competitive teams are exactly that—competitive—girls are encouraged to try out and see what they can do, and any interests will be accommodated either through fielding division 2 teams, or developing a recreational program. The school sees athletics as central to learning, and supportive of building identity and developing healthy peer relationships. “It’s not just about making you a better volleyball player,” says Ms. Jameson. “We bring those intangibles that sports bring to kids: leadership; organizational skills; cooperation; mental, social, and emotional skills. Much of it comes from that feeling of belonging to the school in ways you don’t get just from being a student. For some girls it’s an integral part of their experience at BSS, and it can make their school experience.”

All the programs, from recreational to competitive, are ultimately—and quite rightly—viewed in light of those developmental needs. “Physical skills and fitness are important, as a healthy body supports a healthy mind,” says Ms. Sheila Allen, Director of Athletics for the Junior and Middle Schools. “The physical challenge of athletics is just one piece of the puzzle ... not every BSS girl wants to be an elite athlete, but every BSS girl can be engaged in physical activity and reap its benefits.”

When we toured, we came across a class of girls grimacing through a five-minute wall sit in the hallway outside the fitness centre, though it soon became apparent that they were having more fun than it might have initially seemed. Once done, the grimaces turned to smiles and companionable jocularity. All good. Challenge and fun are promoted as two sides of the same coin, and that instance was an example of the concept in action.

There is a full-time trainer, who girls are free to access during spares, though they also attend personal fitness classes. The athletic facilities are for the most part new and sparkling, including a rock-climbing wall. In the senior grades, everyone takes

Grade 9 phys-ed, which is a requirement of the Ontario curriculum; however, students are also required to take an additional year of physical activity.

“Everyone has a place here, everyone is good at something,” says a student, “and we all get to find out how to be our best self—which doesn’t mean having to be the best. I love how much I have learned about getting along with others and moving past personal discomfort. And I love the friends I have made for life. That’s what BSS athletics means to me.”

Ms. Jameson feels that the all-girls environment contributes to what the athletics departments are able to accomplish, and what they’re able to encourage. “Some girls who would be development players, or not the stars of the team, will come out and stay on as a development player to learn and participate” because they’re not being compared to the boys teams, and there aren’t gaggles of boys watching from the stands. “When you’re doing sports, you’re on display,” she admits, and some of the pressure of that may be lessened in an all-girls environment. A further effect of that, Ms. Jameson feels, is that the girls are more willing to try new sports, rather than just sticking to the one that they’re good at. The force of the programming is ultimately participation. “The reality is that girls drop out of sport typically at 14 or 15,” says Ms. Jameson. “We can change that. Ultimately, it’s not about doing sport—it’s about being active for life, and the wellness piece that comes from being active for life.”

In addition to traditional athletics, there is a separate outdoor education program, and the school promotes the Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award. “We took a train, to a bus, to a ferry, to another bus, then biked around the island for a couple of days,” says a student of a Duke of Ed trip she took to Pelee Island. “And I got my bronze pin!” she says, clearly delighted at the thought. There are other trips throughout the school year, with outdoor and camp experiences used to promote bonding within the grades. The trips are often taken to established, traditional camps, including Camp Wenonah, YMCA Camp Pine Crest, and others, varying somewhat year to year.

Pastoral care

“Without all the opportunities in arts and humanities, I would have gone and been an accountant,” says a Grade 12 student, not entirely tongue-in-cheek. “It really opened my eyes.” She admits that, when she arrived at BSS, she wasn’t prone to participation in the sciences. “It’s definitely something that I didn’t see myself doing. But then I realized how much of a passion it was to me. And the teachers really pushed me and really made me understand that this is something that I could do.”

Post-secondary planning begins early and is consistent throughout a student’s high-school experience. “In Grade 9, I was given a guidance counsellor, Ms. Wong,” says Spencer, a graduating student. “And she knew right from the get-go what I wanted to do. So we created a plan as to what courses I need to take, what I need to do in terms of hours, and what I need to do in terms of figuring out what to write. And in Grade 10 we’re required to do a careers course matched with civics. For the first part of the year we fill out some personality tests, see what we want to do, and do some research on the schools. And then I did a project [based on that]: I see myself going here, and this is why, and this is what I’ll be taking. So, it definitely starts you thinking early so you’re sure what you want to do.”

The school hosts careers breakfasts eight times each school year, bringing in parents and alumnae to share their experiences and their career paths. They are grouped according to interest: engineering, the arts, the sciences, etc. “We’re particularly interested in ensuring that the people on the panel didn’t have straight paths,” says Dr. Terpstra. “So that people could see themselves” and that there is room for ambiguity and growth.

Spencer ultimately enrolled in a university in the US. She says she chose the school because of its tier-one scientific research facility, which allowed her to be a student emergency medical technician, as well as its strong liberal arts focus. “I am required to take courses that aren’t for my [neuroscience] major,” she says. Some of the courses she’ll be taking are in music, musical theatre, and music production. All of those interests—from the breadth to the foci—she credits to her time at BSS.

The program of care is engineered to create stories like that, through aggressive mentorship, career and academic counselling, and emotional support. All students have access to academic, social, emotional, and post-secondary counselling, as well as study skills development through the learning centre, which is staffed by two full-time learning resource counsellors. Each student has a guidance counsellor, who they tend to visit most often around academic counselling. They also take part in TAG, meeting with a teacher advisor once a week for half an hour. “You might [have] a topic, say, around study skills at exam time,” says Ms. Laura Poce, Head of Student Services, “but it might also just be ‘How are you today?’ and do the check-in.”

The opportunities to check in are many. From 10 to 10:30 a.m. each day, students spend their community time either at chapel, TAG, house meetings, clubs, or meeting with their guidance counsellor. “Sometimes it’s just free time,” says Ms. Poce, “and that’s okay. If that’s what they need, then that’s what they need. And that’s fine.” The Chaplain offers spiritual support to any girl who seeks it, and those supports are for all students, whatever their faith. The chapel offers quiet time and space in the students’ busy lives.

There is a school psychologist who attends two days a week. She consults for the entire school, JK through Grade 12. As needed, she’ll see students, though she also works with teachers and sits in on students-of-concern meetings that happen once each week.

“Our offices are as confidential as they can be in a school,” says Ms. Poce. “We often say to the girls that part of their care is their parents. So, there’s lots that we don’t have to necessarily tell parents, like if they’re getting into a bump with a friend or whatnot. But if they’ve fallen behind in work, if we’re noticing anxiety, absolutely parents are notified.”

There is indeed a pronounced attention to not only bringing parents into the equation, but providing resources for them, especially as students advance through the experience of the teen years. “It’s a pretty intense time to be a teenager and it’s a pretty intense time to be a parent. So we do a lot of parent evenings on more of the social/emotional issues.” The school brings in psychologists to give talks and speakers from the Pine River Institute to talk about addiction issues, and it also holds information nights that are less weighty.

Discipline “tends to be a case-by-case [matter],” says Ms. Poce. “There’s disciplinary action, but it will take into account whether it was their first offence, the context around the behaviour. Were they dared? When we deal with issues, for example, of plagiarism, there’s a cultural component to that, and you really need to educate kids around the idea that we don’t want them just to repeat things. So, again, it’s always a case-by-case sort of thing.”

Getting in

“I really liked their selection process,” says Ms. Liz Pullos, a parent of two students who enrolled in 2017. “They asked a lot of really good questions in the written application, including things like ‘what chores do you have to do around the house?’, which I thought was really good—that it wasn’t just, you know, ‘what sports do you play?’ and ‘what are your marks?’. There was good diversity in the questions they were asking.”

The intention at BSS is to gain a wider view of the child, both academically and in life. There’s an implicit understanding that the wider, more personal view, is something that independent schools can at times lose track of,” They will see students more for what they achieve—that an A student is an A student—rather than who they are, and the issues they may be dealing with alongside their academic lives. The approach is one that intends to give each student an opportunity to grow in all areas: academics, social integration, and personal interests. BSS aims to function as a turnaround school, one which brings all learners to the apex of their potential in academics and beyond.

As such, the admissions team is keen to look at the social and emotional context of the child, as well as their fitness for the culture of the school. Says Ms. Pullos: “They also asked lots of questions with regard to her understanding of gender equality, in very age-appropriate ways, but they asked her questions like ‘what do you think about girls not having access to the same rights in some situations as men and boys?’ … and that was really important to me, that they were right onto women’s issues, and that was important in their selection criteria. And that they had families and girls who were aware of that.”

“They have a certain type of girl they’re looking for,” says Michelle Pollock, a parent of two students in the Junior School. “If they don’t find the right fit, they don’t jam the classes full. They don’t just fill the classrooms, which I really appreciate.” In Ms. Pollock’s case, that was particularly apparent—she had visited the school with her daughters outside of an intake year. Nevertheless, “they called us and asked us if we would consider applying.”

Without exception, parents we spoke with commended the admissions process. A visit to the school is highly recommended, if only because it allows an experience of the administration, who are adept at rolling out the red carpet for all visitors, potential families among them.

Money matters

Tuition is commensurate with other schools within the immediate market and across the country. The school community believes that it’s important that girls have access to education, and to that end, some financial assistance is available to students enrolling within Grades 7 through 12. The financial assistance program helps ensure that girls who reflect the school’s mission have access to the programs offered there. Some annual scholarships are also offered. BSS offers the highest amount of financial assistance of all the girls’ schools in Canada. In fact, 10% of students receive some form of financial assistance.

Parents and alumni

It’s typical that any school of the stature and style of BSS will have an active parent council, and indeed that’s the case here. There’s a shared belief that the families are part of the school as well, that they share the values, and that education is about working together, as opposed to a transactional arrangement, where girls are given to the school to be turned into something.

What’s less typical, if not outright rare, are the range of opportunities for involvement. For one, the parents have a book club as well as informal parties, get-togethers, welcoming events for new families, and on and on. “The range of things you can be involved in as a parent,” says Ms. Pullos, “is very widespread. There’s the book club, and through that I was invited by another school mom to go to her book club that she’d had running for 25 years. So, yes, I have enjoyed myself immensely, and I really feel that we’ve landed at the right school for our family.”

Parent and alumnae involvement in volunteer roles is welcome and clearly enjoyed by those who take part. These range from the typical sorts of roles, such as those within the parent council, to leadership roles in fundraising events, such as the annual bake sale. That said, administration is open to other, less typical roles. Alumnae are welcome to take an ongoing role in the life of the school, and indeed many do, from speaking at career events to, as in the case of Ms. Lee, mentoring students who have an interest in her profession.

The school sponsors information nights and workshops, brings in speakers on topics relevant to families of the school, and includes parents as much as possible within the annual calendar of school events. Alumnae events are also sponsored by the school, and they happen with regularity, both in Toronto and around the world.

The takeaway

The Bishop Strachan School has a long and impressive history of excellence, and has consistently provided leadership in education and beyond. This is a school that seeks to give girls confidence in their skills and abilities, and to have their ideas heard in what can be, at times, a very noisy world. There is a strong arts program, and the school emphasizes science, technology, engineering, and math—professions in which women remain underrepresented.

The school promotes the concept that girls need not choose between either arts or sciences, but can each find their own ways of excelling in both, based on the development of creative thinking, effective communication, and ethical leadership. Faculty believe in the value of diversity, and that getting students to think in different ways is a shared responsibility. They are prone to work beyond school walls, interacting in substantial ways with the people, ideas, and cultures beyond. A parent told us that “our experience with the school has been that they are teaching the girls that they are part of a larger community, and that there’s a lot of opportunity to do good.”

The school’s approach, largely, is based in an understanding that it’s a complicated world, one which requires a set of complex foundational skills: thinking for yourself, working co-operatively, and engaging empathetically with others. Coding is important, but so is an ability to write well, speak well, and appreciate the elegance in a well-crafted argument. At BSS, students enter a community of true peers—those who share a sense of curiosity and, while not being bookish, are inclined to academics and respond well to a challenge while appreciating support. Once here, they find those interests shared and rewarded. “There’s very little pressure to conform at a girls’ school,” says an alumna. “Being unique and having deep interests is what’s considered cool.”

The academics are not only strong—they have long provided an example that other schools have sought to emulate. That said, there’s a belief in being able to relax too—that it’s a journey, not a race, and that it’s as valuable to look around as it is to look forward. In terms of skills, outlook, and confidence, girls leave the school ready to take on the world. And they do.