Trinity College School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Trinity College School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Our Kids editor speaks about Trinity College School

Basics

Trinity College School is a co-educational, independent boarding/day school located in Port Hope, Ontario. It offers a liberal arts education and includes a junior school, comprising grades 5 through 8, and a senior school, comprising grades 9 through 12. The stated mission of the school is “developing habits of the heart and mind for a life of purpose and service.” Which is a bit of a mouthful, but that mission is apparent throughout the school, now more than ever, both through a dedication to values and engagement, and through the development of programs that bring service learning to the fore of student life.

Stuart Grainger has been the head of school since 2004, one of a long line of impressive leaders. Where the earliest head masters were very much leaders of their time—the school’s first, Charles Badgley, took boys out to dig for fossils, per the Victorian craze for natural history—Grainger is as well. Prior to arriving at TCS he served as head of school at Bayview Glen, was head of the junior school at Hillfield Strathallan, and taught at Ashbury College. During his tenure at TCS there has been a considerable capital development, seen most recently with the opening of the Arnold Massey ’55 Athletic Centre. He’s a great communicator, very outgoing and informal. He speaks quickly, and is unabashedly confident in what TCS can offer. (“I’ve had three kids here and they happen to think it’s the best school on the planet.”) He doesn’t conform to whatever image you might have of what a head of school might be. He’s affable, and clearly comfortable in social settings. He’s universally liked by the students, all of whom he appears to genuinely know by name. Which is impressive, given that there are over 560 of them. He maintains a blog with regular, well-composed entries. It’s not essential, of course, but it’s a nice touch. It signals a commitment to engagement, something that defines Grainger’s term at the head of the school.

A visit to the campus is highly recommended, and visitors are welcome either at open houses or by appointment. School tours are given by the students, which isn’t unique to TCS, but is always so great to see. It signals a confidence in the program and the work of the school, and a transparence with all of that. The pride and responsibility that students feel is palpable. At TCS the touring program is known as the Master Key Program, because it’s precisely that: the student guide is given a key that literally opens every door in the campus, from the classrooms, to the dorm rooms, to the head of school's residence. It’s particularly thrilling for a student in Grade 9, say, which was the case when we toured. He took us into a dorm room that was messy, then one that was neat. The students conduct the tours with obvious respect for the school, delighted to have a chance to show it off. Our guide said that “the one thing I really want people to know is about the community feel, and the culture that is here. When you go out during the day you see everybody in the learning commons, talking, hanging out―you just get a great feel.” He clearly means it. And you do. You can’t learn if you don’t feel happy, healthy, and valued, and students regularly confirm that they feel all those things.

“When you go out during the day you see everybody in the learning commons, talking, hanging out—you just get a great feel.”

TCS supports and encourages a range of learning styles, from experiential learning, to peer collaboration, to one-on-one instruction and mentorship. The campus sits on a 100-acre parcel of land on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, and the school makes good use of the abundant green space within its science and outdoor education programs. “We live and learn in nature,” says Barb Piccini, head of the junior school.

A majority of the senior school students board on site. “Trinity is a boarding school with day students,” says student Ryan Kirkaldy, as opposed to “a day school with boarding students.” That was important for him and no doubt many others. “I couldn’t see myself in a place where the school just clears out on the weekends. That was a big thing.” (He’s also a fan of the sushi bus. “On Saturdays we have practice and on Sunday there is a shopping bus that goes to malls in the Toronto area. They have sushi and movie busses on Saturday nights.”)

The culture of boarding very intentionally and consciously informs all aspects of school life. “Of course we have no boarding in the junior school,” says Piccini, “but it’s the mentality of it. It’s not rush, rush, rush to begin; it’s not rush, rush, rush to get to the end of the day. We’re here.” She means that in the small ways, such as the fact that teachers tend to arrive early and stay late, and that there are always snacks available via the dining hall. But she means it in the larger ways too, as in the sense that there is always life on campus. It is a place where people don’t just sleep and study, but truly live. “We are a boarding school,” she says, “and somehow or another that filters into the life of the school.”

There are six boarding houses on campus, each including a housemaster who also lives on site. At the moment, all of the housemasters are in residence with their families. “All of them are raising kids on campus because they believe in the place,” says David Ingram, a member of the teaching faculty and senior housemaster. “And I think that the families of our students like the fact that the school is such an important part of the housemasters’ lives.”

All of those things—the space, location, and the residential culture—contribute in positive ways to the lived experience of the campus. The environment is active, engaged, diverse, and cross-generational. The ethos, for the most part, is lightly Anglican. There is chapel each morning, and it is mandatory, presided over by Father Don Aitchison, an ordained Anglican minister. “Though it’s an Anglican service, there is a significant community piece that happens in chapel,” says Ingram. In practice, it’s more about that community piece than it is religious observance. There are skits, and regular recognition of student achievement. “He takes the religious part of his job seriously,” says Ingram of Father Don, “but the other part of his job he takes seriously, too: connecting with young people, being a confidant, being a resource.”

Key words for Trinity College School: Tradition. Identity. Community.

Background

From day one, the life of the school was lively, and not at all the kind of environment that we might assume was common to Victorian era boarding schools. It’s easy to be charmed by the accounts that exist from that time. Instructors included the “handsome Mr. Litchfield,” and Mr. Sefton, “a very jolly Englishman who knew all about church music.” Sergeant-Major Goodwin was “a thorough old soldier who boasted on having attained his 18th birthday on the very day that he fought at Waterloo, was adored by all the boys. … when he was not teaching [he] always had a bunch of boys round him who listened with delight to his many stories of military life.” Goodwin established the school’s cadet corps, and drilled students in the use of cavalry swords “which were worn with a great deal of ceremony going to and from the drill ground.”

One of the best records of early school life is the diary of student Peter Perry. His first entries are delightfully enigmatic. One reads, in its entirety, “I had an accident with gunpowder.” After the move to Port Hope his entries become more detailed, and offer a very candid view of life at the school. “Thursday, [April] 12th. Rainy all day. Dinner: veal and roly-poly. Did not take any pudding. Mr. Badgley's table did not take any because it was so bad.”

TCS began in 1865 in a rectory in Weston, Ontario, and was created to offer an Anglican education to boys in the area. It was called the Weston School, and was founded by Rev. William Arthur Johnson, a man who was, in every conceivable way, a product of his time. He was born in Bombay, India, where his father was posted as Quartermaster-General to the British forces stationed there. When his father retired that post in 1819, the family moved to a parsonage near Bromley in Kent, England. William was granted an education appropriate to his class within a very class-conscious age: he was groomed to take a place in the administration of the commonwealth, just as his father before him.

But, it wasn’t to be. Instead, William came to Canada seeking adventure, married Laura Jukes, and moved into a log cabin that he built for her with his own hands. He farmed a bit, took part in the rebellion, and otherwise sketched and painted watercolours. He also studied plants and insects, which was something of a fad at the time, though Johnson indulged his passion more than most: his collection of nearly 1600 microscope slides was later donated to the Academy of Medicine in Toronto, where it remains today.

At 30 he decided to join the clergy, and the service he offered his congregation lead to a decision to start a school. In the first term there were nine students and a faculty of four. His three sons were the first students on the register, and he took in the sons of friends as well. The register has been kept to this day, and all students are placed on it when they enter the school. Albert, Johnson’s eldest son, is #1. Sir William Osler is #27. Frank Darling, who would one day become the architect of the school buildings (as well as the architect of U of T’s Convocation Hall, Victoria College, and the Bank of Montreal building which now houses the Hockey Hall of Fame) is #17. Peter Jennings, the ABC news anchor, is #4150. Businessman and philanthropist Edgar Bronfman Sr. (#3786) attended at the same time as the philosopher Charles Taylor (#3985). Reginald Fessenden, inventor of the radio, is #847.

To underwrite growth, Johnson applied for a partnership with the corporation of Trinity College, now part of the University of Toronto, and with it the name was changed to Trinity College School. Johnson set the tone for the school, one that is felt to this day. He emphasized outdoor education, taking boys on field trips, sharing with them his enthusiasm for natural science along the way. His approach was that of growing knowledge through engagement. “[Johnson’s] concept of education did not lie in the greatest number of facts that could be drilled into his boys,” wrote A. H. Humble, an early historian of the school, “but in ideas and pursuits that would stimulate and excite the unfolding mind.”

“[Johnson’s] concept of education did not lie in the greatest number of facts that could be drilled into his boys, but in ideas and pursuits that would stimulate and excite the unfolding mind.”

The school came into prominence under the leadership of Charles Bethune, who reluctantly accepted the role of headmaster in 1870. Reluctance is perhaps too kind a word—he was fairly irascible, didn’t love the thought of a life in administration or even education, and the school was dangerously in debt. “When Dr. Bethune became head master,” wrote the editor of The Record in 1899, “there was only a wooden building on the present site, and the school work was conducted in rooms in the town.” The first task was to literally build the school and grow the enrolment. And he did. By the second year Bethune had increased the student body by half, and by 1872 they were moving into the first building created specifically to house the school.

There was a renegade, frontier spirit in Bethune’s leadership, and one that he also brought to the school’s programs. At most private schools at the time, chapel sermons were no different than what you would hear in a typical church. At TCS, they “went far beyond the limits of time for ordinary sermons [yet] held the boys in rapt attention.” In one, the Archdeacon Vincent of Moosonee spoke about life in the north, and afterward “there were few, if any, who … did not think to be a missionary in Moosonee would be one of the happiest things possible.” (One student, R. J. Renison, actually became one.)

Bethune ultimately stayed on in the role for 29 years, something that even he seemed to marvel at. It was a period during which—as a result of his leadership—the school was incorporated and grew in size, stature, and reputation. Soon, students arrived from Iowa, Montreal, and even the west coast, despite the fact that the Canadian Pacific Railway had yet to be completed. Students loved him. He was seen as kind and fair, something he imparted to the character of the school he developed. One of the most moving and repeated moments in the school’s history is when Bethune arrived at the 50th anniversary celebration in 1915 and was given a spontaneous, lasting ovation.

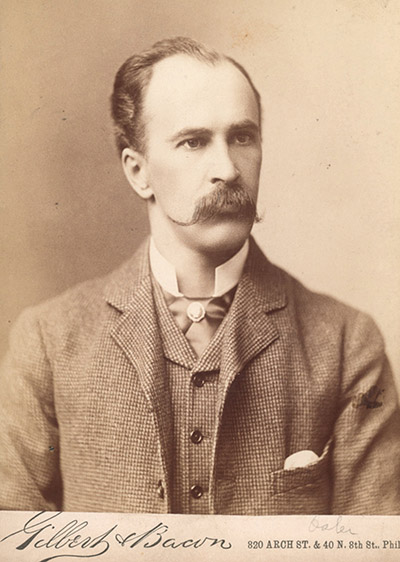

William Osler was the first head boy at Trinity College School, one of a long string of impressive achievements that he was to chart over his lifetime. He later became co-founder of Johns Hopkins hospital, and was knighted in 1911. The thing he is rightly best remembered for today is his impact on how medicine is taught and practiced. He believed the best approach to care was an empathetic one, and that it was best learned at the bedside. The result was the concept of the medical residency, which remains the cornerstone of medical education today. Osler’s seminal work is The Principles and Practice of Medicine, a book he dedicated to William Arthur Johnson, his teacher and the founder of TCS.

William Osler was the first head boy at Trinity College School, one of a long string of impressive achievements that he was to chart over his lifetime. He later became co-founder of Johns Hopkins hospital, and was knighted in 1911. The thing he is rightly best remembered for today is his impact on how medicine is taught and practiced. He believed the best approach to care was an empathetic one, and that it was best learned at the bedside. The result was the concept of the medical residency, which remains the cornerstone of medical education today. Osler’s seminal work is The Principles and Practice of Medicine, a book he dedicated to William Arthur Johnson, his teacher and the founder of TCS.

The school today

“My uncle is that gentleman up there,” says Steph Feddery pointing to one of the portraits that look down from the walls of the dining hall. “My family would come down and spend holidays here. I lived in the Lodge for about six months at one point, and my aunt was the archivist at the time, so I picked her brain a lot. It is fascinating, when you look around and see the history and the names.”

The history provides a sense of tradition and place, one that the administration rightly seeks to maintain. “When we created the strategic plan,” says Stuart Grainger, “we asked ‘What is going to be the key to Trinity College School?’ And no matter what is going on in the world, we have to stand for integrity, compassion, kindness. And those values are referenced from 100 years ago. The history is in a series of personalities that sat in the same place that you are sitting in now. So that appreciation, respect, value-oriented leadership, value-oriented living, still remains as fundamental to living a purposeful life.”

“ … no matter what is going on in the world, we have to stand for integrity, compassion, kindness. And those values are referenced from 100 years ago.”

Feddery has had a front-row seat for a considerable amount of its recent development, despite still being young. She enrolled in 1991, entering the school with the first cohort of girls—TCS was a boys’ school for the first 125 years of its life. “My brother had already been here for a year, and it was very overwhelming because there was a lot of animosity toward us. … a lot of the seniors were bothered when the girls arrived. Of course, some welcomed us with open arms,” she says, chuckling as she does.

“Things changed, and things were supposed to change anyway, but bringing in the girls exacerbated that. … But I had a great time, and made awesome friends that I’m still friends with today. It’s an experience. I was living away from home. I had focused tasks that I had to accomplish here: routines, schedules. And because there was a small group of girls—there were 60 of us in the first year—we were all in the same boat, experiencing the same things.”

The inclusion of girls within the student body paved the way for more women on faculty, of which Feddery is an example. She’s also the master of Wright House. “Having female role models in the science and math classrooms has really helped,” she says. “When I was here there weren’t very many female teachers. There were a few, but I didn’t happen to have them.” Unlike when she began, the school now has a history of coed education, with photos and paintings of girls and women up there on the walls with the men, something that Feddery feels is important. She’s up there too, in a photo from her days on the volleyball team. “My students used to mock me incessantly. ‘Miss Feddery I see you on the wall!’ … But just for them to see that you’re an alum, I think it’s very powerful.” Also unlike when she arrived, the faculty today is evenly split between the genders: “I think for girls to see girls in science and girls in math is quite powerful.” Certainly, boys benefit, too, if less overtly.

Student population

There is an annual enrollment of 560 students, with 460 in the senior school and 100 in the junior school. More than 60% of the senior students board on site, with well over half of them arriving from 35 countries overseas, give or take a bit. The school is dedicated to diversity within the student population, and a robust program of financial aid is the main means of developing it. It’s the second largest scholarship and bursary program of its kind in the country.

The general atmosphere is one of students who are thoughtful, confident, and appreciative of the opportunity to attend the school. There are perhaps schools in the country where privilege is the main takeaway, though TCS isn’t one of them. We asked a student if there was a dark side, and she seemed very honestly unable to come up with one. After some thought, she said that there’s a door between two areas of the school that, if you’re not careful, can hit you as you go through. So, there really isn’t much of a dark side, it would seem.

“I'll never forget my first day of grade 9,” says Jocelyn Murphy. “Looking up in Osler Hall and seeing some forty flags hanging from the ceiling. Around me was this incredible mini United Nations of kids and I felt like the luckiest person in the world.” As throughout the school’s life, it remains today a unique window onto the wider world, and Murphy is a particularly good example of the benefits of that. She went on to study internationally, and has spent her career in the service of the international community. Since 2015 she’s been working for Medecins Sans Frontieres in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Pakistan.

“Around me was this incredible mini United Nations of kids and I felt like the luckiest person in the world.”

“For lack of a better explanation,” says Murphy, “I was a very bright student in high school and academics came easily to me. My teachers recognized this, along with the fact that this brightness made me lazy at times. At TCS she was pressed to take Advanced Placement courses, study languages, and to be involved in areas beyond her core interests, including equal representation of humanities and sciences. “My teachers recognized my abilities and my weaknesses and supported me to tailor my course load accordingly. … [it] taught me the importance of challenging myself to strive for something greater when I went to university, as there was no one there to hold my hand.” In that she’s perhaps typical of students who attend the school. They are bright, capable, yet needing a bit of inspiration and pizzazz to truly motivate them to reach further and achieve more.

The boarding experience

“Everything I need is here,” says one student, but it’s more than just food and bedding. “I’m happy and comfortable here because I know I belong.” If there’s one thing, in our experience, that TCS does particularly well, it’s that sense of belonging. Students aren’t confined to campus, and the service learning programs offer an interface between the school and the surrounding community. Still, Port Hope isn’t large, and therefore it doesn’t upstage the school in the view of the students: the town experience is ancillary to the campus experience, rather than the other way around, as can be the case in schools located in larger urban centres, and which have larger percentages of day students.

The school feels like a lively, complete, cohesive village. Which for the most part it is. When a student says that “everything is close by,” it’s a reference to all of that: the essentials, as well as a true social life, and an ever-present context of support.

“I’m busy every day of the week,” says one student, and that’s universally true for all. The administration works to ensure the right level of busyness, so that students are engaged, and get their beans out, but don’t feel that they are being run into the ground. It’s also not an environment that implies that busier is always better. Students are given time to relax. The school understands that the most successful student is one who has time to breathe, to interact with others, and to rest. That maybe seems like an obvious thing, but not all boarding schools are successful at getting the balance right. TCS does.

Programming on the weekends tends to be engaging but light, with participation in co-curricular activities and special programs and events throughout the school calendar. “They might get on a sushi bus, or go shopping, or go to the zoo,” says David Ingram. The sushi bus comes up a lot when speaking with students. It’s clearly a hit. “But at the same time, this is a very busy place, so we intentionally don’t pack our weekends, and are deliberate about not mandating too much on the weekends, save for the co-curriculars.”

Boarders feel that they are the core cohort of the school, and report a high level of satisfaction with the boarding experience. “It exposes you to so many experiences that you usually wouldn’t be able to have,” says student Nathan Titterton. “I have friends from all over the world, have been exposed to so many other cultures and done things that I never would have even thought of doing prior to coming to TCS.”

The academic environment

Class sizes are on the smaller side, typically in the 12 to 20 range. Technology is a component of all the learning spaces, with Wifi and Smartboards throughout, as appropriate. Students in the senior school are required to have a laptop, and communication, research, course information, and many assignments are completed, submitted, and reviewed online.

Formal exams are held in June in the eight days leading up to Speech Day. Students are required to write them, and they range from 1.5 to 3 hours, and provisions are made for learning or attention differences. Exams are worth between 10% and 30% of the final grade.

“We’re carrying 121 different courses,” says Myke Healy, Director of Teaching and Learning. That’s a hefty amount, particularly for a school of this size. There are also 21 AP courses on offer. The intention, says Healy, is to maximize choice. “If a student can pick their courses, there’s a commitment to the learning.”

“If a student can pick their courses, there’s a commitment to the learning.”

TCS is one of 10 schools in Canada chosen to pilot the Advanced Placement (AP) Capstone Diploma, a two-year program of study for Grade 11 and 12 students that emphasizes critical thinking, collaborative problem solving and research skills in a cross-curricular context. “We know that fostering curiosity, encouraging a thirst for knowledge and teaching our students to be receptive to change, will serve them well for the unforeseeable future,” says associate director of admissions Adrienne Ross. The AP Capstone Diploma enriches the Ontario Secondary School Diploma (OSSD) by further preparing students for university and provides TCS graduates with the opportunity to distinguish themselves on international university applications, particularly in the U.S. and U.K. “Collaborative learning, problem solving, perseverance, compassion,” says Ross.“Those are the things that will give them a strong foundation when they leave the school.”

Part of the Capstone program is a research project that is conducted throughout the grade 12 year. Molly Dunn, a day student with an interest in film and theatre, chose to look at the film “Suicide Squad.” “I was looking at its portrayal of a relationship between two characters, and how that influences the audience’s perception of abuse.”

She continues, “it’s definitely a unique course. I never imagined that I would ever be investigating something like that, and getting that kind of experience. And it’s a very challenging course at times, but at the same time, it’s so worth it.” Her experience reflects well on the dedication of the faculty to making it as rich as possible. Dunn was put in touch with a professor of film studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “The teachers for our course helped me with initially reaching out to him, and helped me through that process as it moved along.” It included working with him to develop a survey, among other things.

Dunn is clearly jazzed about the entire thing, and when she talks about it, there is a sense that she wants to pinch herself to confirm that it all really happened. That’s because of the people that she was in contact with, but also because of the support that she received—that her ideas weren’t only taken seriously, but that faculty worked so closely with her to take them farther than she could have imagined at the outset.

The school rightly prides itself on offering a range of leadership and service learning opportunities, both within the school and in the surrounding community, building skills while encouraging students to find their own voices and to put themselves forward within the student body. “At the beginning of the year you have kids that come in who are scared to death,” says Bill Walker, director of arts. “They’ve never done anything like this before. They’ve never had to talk in front of their peers before. And slowly but surely, that level of confidence gets fostered, so by the end of the year—whether they’re giving a monologue on stage or they’re giving a report in a history class—I know they’ve got their legs under them. And that’s really what we’re aiming to do.”

“It’s really helped to bring me out of my shell,” says Sharon Omiwole, a grade 12 day student. “I used to be a very, very quiet person. But I feel I’m able to talk more, and especially because I do announcements, I have the confidence to give presentations to my peers and teachers. And I don’t know if I would have gotten that anywhere else.”

Academic achievement is highly valued—this is a school, as many will tell you, where it is cool to be smart—though tolerance, personal expression, and consideration of others are equally important. Achievement is also regularly rewarded. “I have a citizenship pin,” says grade 10 student Ben Traugott, “a few scholar’s pins, remembrance day, the arts pin, captain of the swim team.” Those, as well as recognition in chapel, are means of letting students know that their efforts are recognized, something which permeates the delivery of the program. Says Ryan Kirkaldy, “In my grade 10 year I got a letter of commendation from Mr. Grainger because in grade 9 my academics weren’t really that strong, and grade 10 was a really strong year for me. I really appreciated it because Mr. Grainger noticed my improvement throughout that year and I got a letter of commendation, we had a meeting. He talked about how he’s seen me grow. It was a really good feeling for me, because I had been working hard that year. So, to get that letter was great.”

Is it possible to be a happy, fulfilled B-student at TCS? “Absolutely,” says Grainger without taking a beat. “University stats and all that kind of stuff, that’s not where we’re truly satisfied. I think if you’re a genuine educator and a genuine teacher, you just want to have an impact on a kid’s life.”

“University stats and all that kind of stuff, that’s not where we’re truly satisfied. I think if you’re a genuine educator and a genuine teacher, you just want to have an impact on a kid’s life.”

Grainger believes that the best students aren’t necessarily those that arrive with the best marks, but those who can benefit the most from what the program offers. “The kid that you made a difference for.” The one who arrived struggling yet goes on to learn about themselves, their place in the world, and who successfully graduates the program. “Those kinds of stories are our best stories in this school. … the school tries its best to adapt different techniques, differentiated instruction, and encourage teachers to adapt to different learning styles. There is a plan B, and there’s even a plan C.”

The junior school

While elementary grades have been offered at various points in the school’s past, the current iteration of the junior school was founded in 1999 and developed by Barb Piccini, who remains head of the program today. Development has been incremental over the course of her leadership, building programs from grade 8 down to grade 5.

Throughout, Piccini’s goal was to be mission appropriate, challenging, and inclusive of a clear sense of purpose. “I believe that demanding a lot of students is a compliment to them. … Too often [educational] environments are warm and casual, and then they bleed out because that’s all they are. But we have very high expectations for our kids in all areas: comportment, thinking, respect. And we demand of them in a most compassionate and understanding way. And I love the marriage between the two. Which I think is quite unique to this school.”

“I believe that demanding a lot of students is a compliment to them.”

The feel of the junior school is very personal and close-knit. The building provides a charming setting, with the architecture providing an appropriate backdrop to an elementary program. From a child’s perspective it looks like a castle, something that is used to good advantage within classroom decoration and design. There are large group spaces as well as personal spaces for children to read or interact in smaller groups, including one-on-one. Instruction is student driven, and while class work hews closely to the curriculum—as it should—teachers actively take cues from the students, building off their interests, curiosities, and experience.

Service learning

Service learning is a key element of the Ontario high school curriculum, though TCS seeks to better that requirement in both breadth and depth. “We feel it’s how our students give back to the community,” says Kim Vojnov, coordinator of the program, “but it’s not just the giving back piece, it’s also what they learn from it and how they use that new piece of learning to guide future decisions and interactions.”

It’s something that the school has built consistently over the past decade. In addition to individual service projects, each year there is a service week, known as the “Week without Walls” which is dedicated to service in the community each afternoon for a week. They get a repetitive experience, with students returning to the same tasks each day. On the last day the school comes together to present the various things they’ve done. Activities include some of the more typical service work, such as volunteering at local food banks, though there is some nice breadth as well, such as placements with community farms and local wildlife and environmental conservation authorities. Locations include sites within Port Hope and beyond, in a triangle bounded by Belleville, Peterborough, and Toronto.

There are two service trips that are scheduled that week. One is an education service trip, with a dozen or so students travelling Ecuador to work on a Me to We project. The other is an environmental service trip to the Island School in the Bahamas where students take part in marine conservation and study projects.

“So you’ve been out there, you’ve done this, what does that mean to you and what can you do moving forward?”

Learning, not just service, is a key aspect of the program. “We come back in and try to do a debrief, to talk about the ‘so what?’ So you’ve been out there, you’ve done this, what does that mean to you and what can you do moving forward?” Recently, service projects were also offered within the co-curricular program, allowing students to follow a project over a longer period of time. “It’s now as available to students as arts and athletics,” says Vojnov.

The instructional day

Day students arrive from a sizable catchment area, including centres further afield. There are two bus routes, one north to Peterborough, and one west to Ajax. Each day begins, for both boarders and day students, in chapel. The students file in and then the head boy and girl close the chapel doors and take their seats. The students sit quietly, some gazing off into space, though even if they’re still shaking off sleep, there’s a sense of respect in the room. No phones are out. Students pick up the hymn book when the organ starts, they stand, and they sing. “It’s my favourite part of the day,” says one student. “I just like how it brings the school together.” Says student Jaden Love, “there are certain songs that the entire school loves to sing, and when we sing those I just feel better for the rest of the day. It’s a really good way to start off your day.”

“We don't work on a semestered schedule,” says Molly Dunn. “We work on an 8-day cycle: 4 classes one day, 4 classes the next. … “usually during my spares I’ll have a meeting with my guidance counsellor,” she then adds with a chuckle, “you know, to figure out what I want to do with my life.”

The 2016/2017 year saw the introduction of the Flex Block as a regularly scheduled part of the academic day. “We used to have club meetings during lunch,” says Dunn, “but now lunch is just for lunch. During Flex there are various clubs that meet. For some AP classes you have Flex class. So, for example, my AP biology course will have flex class once a cycle.” Every academic day includes a 50-minute Flex Block for additional curricular and co-curricular programming. This is time used for advisor-advisee meetings, extra Advanced Placement classes, experiential learning opportunities, club meetings, music ensemble rehearsals, Grade 9 Touchstones discussions, faculty professional development, house debates, full school activities such as guest speakers, and other activities relevant to the core programs. Flex Block “was introduced to allow lunch to be focused just on nutrition,” says Kathy LaBranche,”as well as finding balance within the days. We had a committee take a look at wellness and balance and an overhaul of the schedule resulted.”

It’s a pretty good day: no commutes, strong interpersonal connections, and a growing sense of independence and responsibility. That independence, and the insight that it can garner, is encouraged throughout school life. It’s a very student-driven environment, one in which learning comes from within and without the classroom. Students maintaining a 86% average or above are free to manage their study schedules, and can study in their dorm, the library, or anywhere else on campus they wish. Students who have less are required to study in assigned classrooms, during prescribed times and under supervision. “Independence is fostered, not assumed.”

“I don't want kids stressed, I don't want them worn out.”

Says Dunn, “After school we have either sports or arts. So in the fall and winter term, I would have play rehearsal. This term I have an arts in service. I work on the yearbook, and this is my second year working on the yearbook. … it’s going to be nice to be able to design the yearbook for my graduating year.” Most students report that, in all, it’s busy, but comfortably so. “I don't want kids stressed,” says Stuart Grainger, “I don't want them worn out.”

Athletics

The athletic tradition is long, and operates to complement the full range of programming within the school. “The goal is to demonstrate the values and benefits of healthy active living,” says Tim White, director of athletics, “and teach important life skills such as commitment, leadership, respect, effort, humility, and friendship.” All students are expected to participate, and to be active.

Sports facilities, as well as a dedication both to competition and recreation, are extensive. Students have the opportunity to participate in competitive athletics within 18 interschool sports and 46 competitive teams. TCS competes within the CISAA league and OFSAA provincial championships. The school fields Bigside (senior), Middleside (senior second team), and Littleside (junior) teams.

The Oxford Cup

“It is a very long, historical race,” says Tim White, and by any definition, it truly is. The Oxford Cup was first run in 1896, predating the Boston Marathon by a year. It was initially a cross-country race run by four boys, each chosen to represent their boarding house. In the early days, the race was truly cross-country in every sense of the word: a 5km course through brambles, over fences and creeks, through forests and across farmers’ fields.

“It is a very long, historical race,” says Tim White, and by any definition, it truly is. The Oxford Cup was first run in 1896, predating the Boston Marathon by a year. It was initially a cross-country race run by four boys, each chosen to represent their boarding house. In the early days, the race was truly cross-country in every sense of the word: a 5km course through brambles, over fences and creeks, through forests and across farmers’ fields.

“It’s gone through various phases of how it’s been run,” says White. It’s not an obstacle course anymore, and the competitors aren’t limited in the way they were in those early days. “In the early ‘80s, when Roger Wright became headmaster, it morphed into today’s version where the entire school participates.” More than 600 runners take part each year, including the entire student body, faculty, friends, and family members.

“It’s really a TCS family and community event,” he says. “It’s pretty unique, and we have a lot of fun with it.” Old as it is, it isn’t the longest running athletic event at the school. In 2017, TCS participated in its 150th cricket tournament with Upper Canada College. The first tournament was held in 1867—the same year that Canada became a country—and the teams have met yearly ever since. “How many schools can say they have a 150-year history of participating in a sport?” says White. “Being part the school, you’re a keeper of that tradition. And although traditions change over time, there are some parts that are important to maintain. Tradition just for tradition’s sake may not make a lot of sense, but there are some traditions that make a lot of sense to keep going.” If the race, or the cricket match for that matter, were just a few years old, White expects far fewer students would be keen to take part. Tradition can be a unique motivator.

Pastoral care

“In terms of the scope on campus, we have about 40 people working with the various residences and houses,” says David Ingram. “The day houses are meant to oversee what happens day to day with the day students, and that means anything from taking attendance, to support, mental health, to facilitating sporting events on campus. It’s all encompassing.”

Given the size and organization of the school, it would be difficult for any child’s issue or unhappiness to go unnoticed for long. “We’re a fairly small community,” says Shelagh Straughan, “and people notice stuff. If there’s a kid feeling off in chapel, I’ll fire a note to their housemaster and just say, you know, so-and-so was not himself.”

“They always know there is someone there to back them up or support them in any way,” says Bill Walker, director of arts. “I think that’s very empowering.”

A walk through the campus when classes are in session provides ample evidence that the students clearly are known and have an easy, amiable relationship with the faculty. There is a comfortable, informal feel throughout the school. “I just love the people and I love the teachers,” says Jaden Love, a grade 10 student, with very heartfelt sincerity. “I love how you feel like you’re part of more than just a school.”

“I can talk to her about stuff that I can’t talk to my parents about … ”

Students are assigned faculty advisors which they meet with regularly both in groups and one-one-one. “I can talk to her about stuff that I can’t talk to my parents about,” says Ben Traugott of the relationship he has with his advisor. “Some people talk about things we’re going through, different ideas we have for the school … we have a great dynamic, and she runs great discussions.”

“Advisors and house masters are the two most significant points of adult contact for the students,” says Shelagh Straughan, head of the advisor program. “Your advisor and your housemaster are your go-to people.” There are 10 houses, and the house system is the foundation for the administration of pastoral care. All students are assigned to houses when they enroll, with separate houses for day and boarding students, boys and girls. Each house is assigned a house master, and peers also provide support throughout the school year.

Chapel is compulsory for all students, and provides an important daily contact between staff and students. The health services department is robust, and includes a school physician, a director of health services, four school nurses, two athletic therapists, and a counsellor. There is a proactive approach, and entry to care can be initiated by housemasters, school heads, faculty, peers, or through self-presentation. Communication between the advisor committee coordinator, guidance counsellors, and faculty is consistent.

Discipline is applied fairly and thoughtfully. “We’re very careful about managing every case as a separate case,” says David Ingram. “If somebody is speaking with an adult and seeking help or recognizing that they've done something wrong, accepting responsibility for their actions--it’s important to us that we acknowledge that as a positive behaviour.” He continues, “I feel that we’re doing a very good job with our discipline, and we are listening to kids” and seeking ways to “help the person grow as a result.” There are expulsions (one of them, in fact, was Conrad Black, who lasted less than a year at TCS) and that comes with being this type of school in this type of system. “But we always look to our objective.”

Getting in

The admissions team wants to be certain that candidates are academically a good fit, and of course parents do too. Students at TCS are required to take part in athletics, the arts, and service learning, and admissions officers are looking for students who are comfortable in all those settings.

Typically, the admissions process begins with completion of an online application. For those applying locally, a visit to the school is strongly recommended. Prospective students are invited to spend a day at the school, with overnight visits also on offer. Again, the best way to gain a sense of a school is through direct experience, and taking advantage of all the various programs, including the overnights, open houses, and interviews, is advisable.

Prospective students are asked to write an aptitude test and complete a writing sample. Applicants are also asked to forward school reports and recommendations. For students enrolling from overseas, the admissions process can be handled remotely, with parent and student interviews conducted via Skype. Overseas candidates may be asked to write an admissions test, and if so, provisions will be made for them to write it within their home community.

Money matters

“You don’t have to be wealthy to apply,” says Tim White. “And if we can afford to help them be here, to help enrich our place, why not? We’re just looking for great kids.”

TCS has an endowment that exceeds $50 million, with the majority of the proceeds earmarked for the school’s financial aid program. It’s the second largest private school endowment in Canada. Aid is intended to ensure that all mission-appropriate students are able to attend, and to allow the school to curate a diverse student population. “As a recipient of financial aid myself,” writes an alumnus, “I certainly felt that my presence at TCS was the great equalizer and that my family's net worth had nothing to do with my ability to be a part of the community.”

One of the great stories of recent years is the endowment by Lewis Cirne, including the creation of scholarships as well as the Cirne Hall—completed in November of 2015, it includes the senior library, administration, and a student commons—which is a focal point of student life. Cirne attended through support from the financial aid program. On finding success, he then gave back to ensure that others would have the same opportunities. It also solidified the place of the aid program within the school, in some perhaps subtle yet substantial ways. The most obvious endowment comes from a student who arrived to the school from the local community and attended through the aid program. For any student who attends via the aid program, that alone is potentially quite empowering, yet also communicates something generally, and very positive, about financial diversity within the life of the school.

Tuition covers the cost of instruction, with additional costs for boarding, uniforms, books, and trips. All senior students are required to have a laptop, something that also isn’t included in the cost of tuition.

Parents and alumni

A password-protected site is used to deliver information about events, grades, and to book teacher-parent meetings. The academic year, divided into two terms, includes five reports and two parent-teacher meeting sessions. Students are assigned a faculty advisor who then becomes a primary point of contact. That and other means of communication, including a parents’ newsletter, create a broad interface between home and school, and parents consistently report that they feel well informed.

David Ingram, Senior Housemaster, notes that the interface with parents is porous, and communication is frequent and varied. “I think that, certainly, for the first little while, they want some pretty regular dialogue and they get that. If we can send a picture home of their child enjoying themselves, that's a positive. But ultimately they become comfortable when their kids become comfortable. If their children are struggling through homesickness, the parents suffer through that as well.”

A Parents’ Advisory Council is operated as a means of bringing parents together to provide feedback on all aspects of the school experience. All junior and senior school parents are welcome to participate in the council.

At least some of the alumni of the school remain fairly rabid in their engagement with each other and with the school. There are a range of opportunities for alumni to keep in touch, including groups in Canada and beyond. Faculty, whenever they are able, attend these events, which is also very nice to see. “Last year, while waiting to catch a plane from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the UK,” says Jocelyn Murphy, “I went on Facebook and saw that Mr. Grainger and Father Don were in London. Next thing I knew, I walked off the plane and into the Canadian High Commission for the London Branch dinner, running into friends from Cuba, Canada, and Hong Kong.” How great is that? Formally and informally, all report that the school has a very high rate of ongoing engagement with alumni.

"...ultimately they become comfortable when their kids become comfortable."

The takeaway

Trinity College School has a long reputation within Canadian schooling, one that no doubt is the envy of many. It’s also a reputation that has been truly earned. Since the beginning, the focus has been both on a strong academic program as well as developing character, interpersonal skills, and a dedication to service. The alumni list includes some Great Canadians, of which the school is rightly proud, though the focus remains on the needs of all of the students, not just those operating at the top of their peer group. When Grainger says that, as educators, “you just want to have an impact on a kid’s life,” it’s clear that he truly means it. The dedication to diversity within the student population, including financial diversity, is evidence of that, and something that the school manages particularly well. He, and other program leaders—notably including Barb Piccini of the junior school—have an energy that they have brought to bear on the life of the school, including a dedication to addressing students’ lifestyles, and an attention to balance as much as achievement. Because of them, as well as a very modern facility that keeps the traditions and values in view, the school has a lot to offer to a fairly broad range of learner.