Crestwood Preparatory College THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Crestwood Preparatory College, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

Crestwood is a preparatory school, whose goal is to nurture individuality while Inspiring excellence. The mandate of the academic program is to prepare students for the challenges that they’ll face at university and beyond. Academics at Crestwood are strong, robust, challenging, and delivered to demand the most of the students—they’ll learn the content, how to work creatively with it, and how to communicate their results.

“Crestwood creates an environment for students to find success,” says Head of School Dave Hecock, “but they’re the ones that ultimately are going to open that door.” Whether In the classroom, hallways or gymnasium, the Crestwood program is built to ensure that students arrive at university with the confidence to advocate for themselves and the aptitudes that will promote success.

While Crestwood Preparatory College was founded in 2001, its true genesis was two decades earlier, in 1980 when Dalia Eisen started Crestwood School. She began with just seven students in the primary grades and the program grew fairly quickly from there. Growth wasn’t so much the intention as was a desire to do something better, to offer something more aligned with what Eisen felt schools should be providing. It was to be, in her words, “a school that could address [students’] diverse needs through differentiated teaching.”

The majority of the students who attended in the early years needed some level of accommodation, though that changed over time, even if the values behind the offering didn’t, which was to meet students where they were, and to find what would work best for each of them. Everything was on the table, though personalized learning—taking the instructional cues from the students themselves—was and is a defining feature. “We initially had trouble defining ourselves and where we were going,” says Head of School Dave Hecock. “But we’ve defined ourselves through our kids. … That’s our job. … I think parents are looking at making sure that their kids have somewhere safe to be.” A place “that they can come and be themselves. That we’re not going to try and change them to make them something that they’re not. That they can come here and be unique, they’ll be well liked, and they can be successful being whoever they are. They can all find their safe place here and feel good about themselves.”

Every school is unique, developing a culture and a character all its own. That’s absolutely true here—and while the primary program shares the Crestwood name, the prep has been allowed to grow, develop, and find its own level. The most obvious examples are the basketball and hockey programs, which, in just a few years, has established itself as one of the premier elite athletic programs in the country. The programs are exceptional, as are the players and coaches who have been drawn to it. If you asked the average Canadian to name a private school in Canada, Crestwood is not the one that would come to mind first—there are other schools with longer histories and more indelible reputations. That said, if you asked someone in the basketball world to name one, Crestwood very well might be the one that they offer—despite its relatively short life, the program has gained national attention and has drawn students from across the country and beyond. Professional ball players, too, come by from time to time to work with and mentor students. If there’s a Juilliard of Canadian basketball, Crestwood Prep is it.

The basketball and hockey programs had their genesis in a problem that all private schools have, namely how to stay relevant in a changing world, and to continue addressing itself effectively the needs of students that, too, change along with the world we’re living in. Mental math, for example, is still a valuable exercise, but it doesn’t have the same gravity that it did before computers or calculators, and a facility with numbers was a key workplace skill. In that, and much else, schools work to continually evolve, while still expressing their initial mandate. They look to do it in ways, too, that express their unique identities, offerings, and communities.

In Crestwood’s case, the administration and the foundation board wanted to address the desire for a broader range of applicants, in turn to bring to the school a broader spectrum of students. Minds first turn to cultural diversity, something that hadn’t been a problem—Hecock notes that the school population has long looked like a microcosm of the Toronto population, if not more so. They knew, however, that diversity doesn’t exist within only those narrow cultural bands. It’s about different ways of thinking, and of seeing and acting in the world.

While it’s not immediately as apparent—at least when driving up to the campus—the Oral History Project, too, has rightly gained significant attention. It also, in a sense, has evolved in similar ways, for similar purposes, as the basketball program—it happened organically, growing out of a desire to offer a richer experience. It’s an initiative of a teacher, Scott Masters, and began as a means of engaging students actively with history, while also bringing it alive through personal stories. At first, they interviewed guests who spoke at the school, including veterans and Holocaust survivors. It grew from there, with students documenting their family histories and cultural heritages through interviews, documents, and photographs. To date, there are more than 400 stories archived. The project, and the approach, earned Masters a Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Teaching in 2012. He’s also a past recipient of the Prime Minister’s Award for Excellence in Teaching and the Baillie Award for Excellence in Secondary School Teaching, for which he was nominated by former students. In 2017, he was awarded Alpha Education’s Catalyst for Change Teaching Award. Alpha Education is an organization that seeks to raise social justice awareness around the Pacific theatre of World War II.

Those two programs aren’t the be-all and end-all of the school, of course, though they nevertheless contribute significantly to a distinctive academic environment. They also provide good examples of how the programs are developed and run, namely with an eye to unique innovation while supporting the desires of a unique, and uniquely engaged, student population. They, as an expression of the larger culture of the school, are the reason that it has such an interesting profile, to be sure, and one that isn’t shared by any other private school in the nation.

Key words for Crestwood Preparatory College: Supportive. Diverse. Dynamic.

Leadership

We asked a teacher what Hecock, the head of school, would say if we asked him what “success” means. She responded without a blink: “happy and productive people.” And indeed, when we asked him, that’s exactly what he said—“happy and productive people!” It’s apparently something of a mantra. Hecock qualified it by saying “we want happy, productive kids that come to school each day knowing that it’s going to be a good day. Now, that’s not very eloquent or profound, but it’s the basis of everything that we do. … We talked about the wrong things for so many years. And a few years ago, I put it out there: We have to start talking to kids about respecting their peers, and about empathy. [The faculty] took it and they ran with it. Without saying anymore, they put town halls together, stuff on their walls and their doors.” There are little speech bubbles posted throughout the school reiterating the core values of empathy, inclusiveness, and kindness.

Basics

Crestwood sits on a five-acre property leased from the Toronto District School Board (on the former site of Brookbanks, a primary school). It’s a prime example of ’60s-era architecture, and there are centennial blocks still visible in the courtyard that reference that time. Crestwood transformed the building into a secondary environment—softening some of the brutalist edges—and, to their credit, there’s no evidence today that it has been anything else. There are purposefully no walls around the grounds, and the back of the campus abuts municipal parkland. That’s symbolic of a desire to interface with the surrounding neighbourhood, which includes residences, businesses, and services. There is a mall next door, and the shops there, at least during the lunch breaks, can feel like an extension of the campus itself. The school sits nicely within its environment, rather than feeling set apart or walled away from it.

The program grew naturally from what had been established in the early days of the Lower School. As the initial student population aged, grades were added to the program. There was a move from that first location to the Bayview Glen campus, a property abutting the Glendon campus of York University. The secondary program, in turn, grew out of that, including the current property. Since then, the programs have been allowed to grow and evolve in order to express the values of the school, meet the needs of students, and capitalize on the expertise of the growing staff. Today, there is no formal administrative relationship between the Lower and Upper Schools, though there is a conceptual one. A majority of the incoming Grade 7s arrive from the Lower School.

Today the school has reached a comfortable size, with just over 560 students spread evenly across the grades. It feels right-sized, with a busy, community feel helped along by the fact that all grade levels are integrated throughout the school. There isn’t a senior area or a Grade 9 area, for example, which provides an entrée to a purposeful program of intergenerational mentorship. The Learning Commons, or LC, is a favourite location for students within the school. “It’s a small, little, quiet place where people do their homework, chat,” a student told us. “It’s just a nice, open space.” Another adds, “everyone hangs out there; even if it’s not at the same time, you see basically everyone go in there. If you don’t know where someone is, you go to the LC.”

The older students run tutor groups with younger students, and the result is less of a divide between older and younger, and more of a neighbour/cousin kind of camaraderie across the age groups. There are both academic and social mentors, formally and informally, and the layout of the interior has been developed to invite those kinds of interactions. The athletic spaces provide an important hub of student life, both in keeping with the prominence of the athletic program as well as the placement of facilities within the building. Conceptually and physically, athletics and athletic achievement are front and centre.

Academics

Some schools really highlight a wall-to-wall program of project-based learning, though assistant head Phil Santomero is clear that “we’re not that.” He notes that they use the inquiry model as appropriate to the learning outcomes and the content, but they otherwise provide a more didactic approach. “We’re a combination of a traditional approach to teaching integrated with some project-based learning,” says Santomero. “We try to keep things hands-on, but I don’t think we are defined by one thing in terms of our academic approach. It’s going to vary based on the course, the teacher.” Unlike some schools that bring delivery to the fore—by organizing around experiential learning or outdoor education, or, in other cases, hew closely to more traditional chalk-and-talk delivery—Crestwood defers decisions of approach, at least in the day-to-day, to the teachers themselves. History, for example, reflects the hands-on approach that Scott Masters (and, in turn, fellow teacher Jason Hawkins) brings to it. And rightly so.

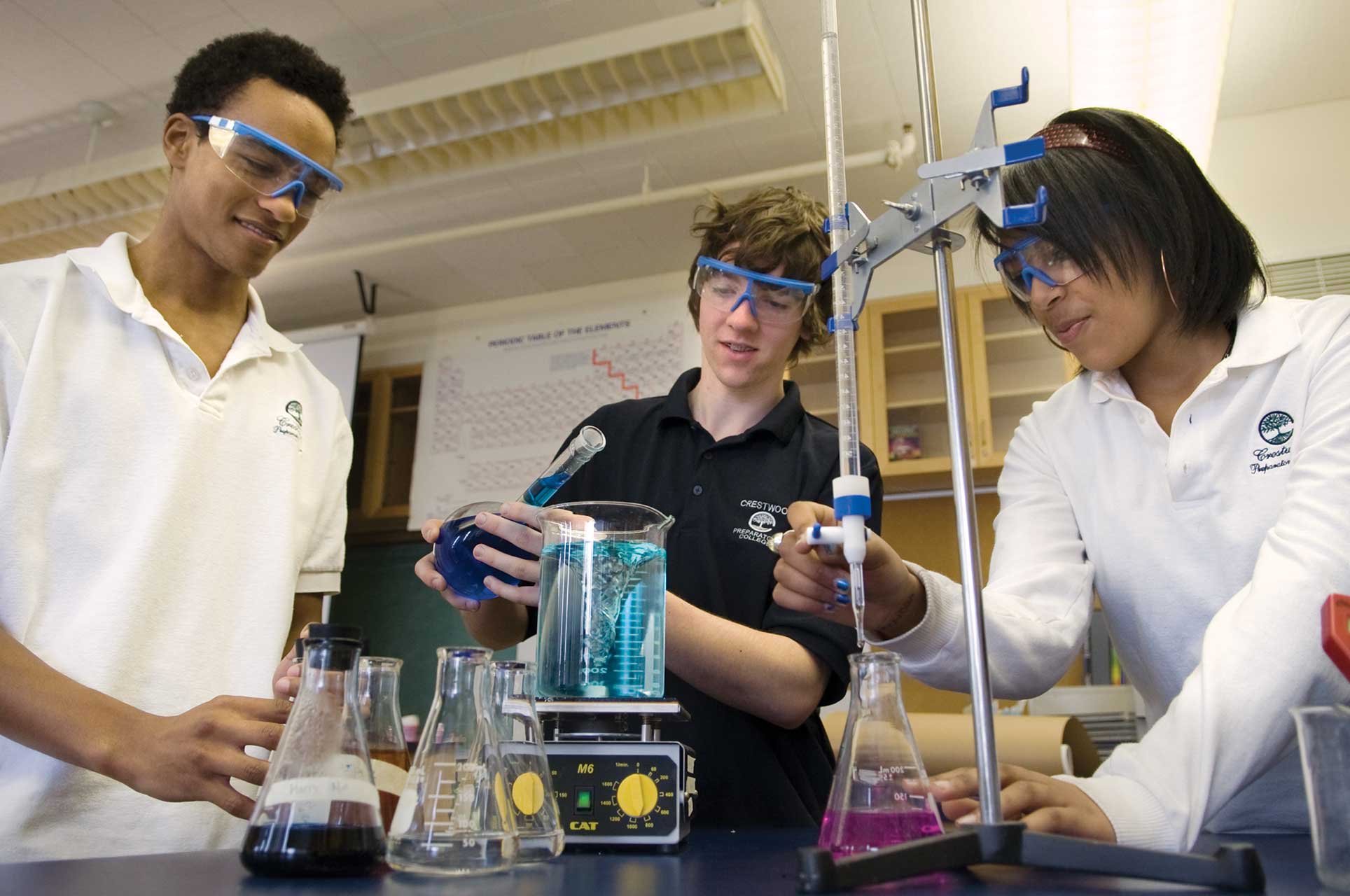

In that, there is an agility to how material is delivered, and a latitude to adapt the content to student needs as well as teaching styles and talents. “The last thing we want is the teacher just standing up in front of the board and giving information,” says Dr. Robert Karisch, head of the science department, echoing a sentiment that is shared often quite vocally with the entire faculty. “There are expectations that we need to teach, but the way we deliver it is up to the teacher.” He also appreciates the fact that courses proceed through the whole year, allowing a longer, and often deeper, involvement with the course content. “Certain things are content driven,” he says, noting that some facts are ones that you, simply; no one is served by rediscovering the Krebs Cycle from first principles, or to physically count the electrons in a carbon molecule. “But as they’re learning about the periodic table, say, they look at how we know the basic properties of it, what are the trials and tribulations that some of these scientists have had in discovering those properties. To dig a little deeper, and not just saying ‘here it is.’”

Says Esther Lee, head of the math department, “it’s about balance [between] the Ontario curriculum, which still puts a huge emphasis on the content, versus a focus on the proficiencies.” Those proficiencies include critical thinking and problem solving, communication, as well as an ability “to look back and reflect on a solution and ask, ‘Where in the process did it go wrong?’” She adds that, “I think we’re more mindfully pushing toward the transferrable sills that students will need.” She’s right, of course. That she uses those terms—mindful, proficiencies, process—are telling of the approach.

The course schedule contributes to a more reasoned pace as well, giving students time to engage more meaningfully with the course content and developing a broader range of skills around them. That includes, in Karisch’s case, written reports with each unit. He feels that while students are used to writing academically in the English settings, they often, in more typical deliveries, aren’t required to write scientifically. Which is too bad, given that communication—reporting results in ways that others can understand, and relating them in context—is an important part of the scientific enterprise. So, when he arrived at Crestwood seven years ago, Karisch built in that requirement, with students writing a research report on a topic raised in each unit of inquiry, and relating it to technology, the environment, and culture. In a chemistry unit, they might look at a product that they use on a daily basis, finding an organic compound within its ingredient list, and then report on what the research says on how it responds to health or the environment. “They’re analyzing it and understanding it, sometimes finding that, you know, maybe some of the things in here aren’t that safe.” The timing that the course calendar allows, he feels, creates space for those kinds of meaningful interactions. “They do take over a month, so they have a large chunk of time where they can really put together something that they’re pleased with.”

It’s one of many strategies used to get at the big ideas—in Karisch’s words “getting students to think differently and to be curious about the ways things work” —and the behaviours that students will need as they move ahead. In a similar vein, faculty nicely look to every opportunity to branch out into the community. Says Masters, “If I hear about somebody interesting out there in the community who I think would be important for the students to interact with, I’ll find a way to bring them in.” Dwight Drummond, a CBC anchor, is a recent example. “I thought it would be interesting for students in my politics class to talk to somebody at work in the present-day media. And he came in and did a really cool presentation. Talking about quote-unquote mainstream media versus social media. Talking about fake news. The stuff that they hear about, what’s going on in the world. … Anybody like that that I come across, I send them an immediate invitation.”

“We’re not putting everyone on the same path,” says Santomero, and he means that both in terms of teachers and students. Just as faculty are free within certain bounds, students, too, are able to find their own path through the material. “We provide an obviously enriched program, though are able to individualize [it] for students based on their own learning styles and learning needs,” he explains. The Ontario curriculum provides the basis and is augmented through Advanced Placement courses and opportunities for students to sit university level exams.

True to its history as an institution, Eisen’s dedication to differentiated teaching—working actively to address and support individual learning—remains a pillar of the Crestwood program. When we asked parents about what the school does particularly well, the individual approach was almost invariably noted first. “My son has dyslexia,” a parent told us, “and they do what they can to accommodate that. They customize and tailor their teaching and their approaches to him.” “They get to know the kids,” says another. “They get to know their strengths and weaknesses” and then support and address them. “’Individuality,” says another parent. “That’s in their theme line, but it’s true. They really get to know the kids and build on their strengths.”

That approach is formalized in the Maximizing Academic Performance Program (M.A.P. Program), which consists of a number of components, including after-school tutorial offices, an English Writing Centre, and an optional General Learning Strategies (GLS) course offered in Grade 9. All are provided to explore learning strategies and social skills to help students become better, more independent learners. Similarly, the ROOTS program allows students to address variable learning through differentiated instruction and individualized supports. Says a student, “classes are smaller; there’s a slower pace. It’s the same material, but I have dyslexia, so it was a better fit than my public school.” Accommodations are also offered to elite athletes, helping them to better balance their academics and the demands of training and competition. There are always kids in every school who are on every team and take up every opportunity, but Crestwood has a particularly large percentage of the student body that is involved in a broad range of activity. “I don’t know why that is,” says teacher Sebastian Major, “but I guess it’s just because it’s the kind of school where kids feel like they can get involved in a lot of stuff. They feel like they’re welcome to be involved in a lot of stuff, and don’t feel that they have to be a jock or an arts kid or whatever. Most of them do it all, which is really nice.”

Students are regularly encouraged to take advantage of the co-curricular program, in part because it can add significantly to the student experience, but also because participation is recognized as a means of developing key skills and supporting academic outcomes. There’s a large array of co-curriculars on offer, from the ones you’d expect (student council, yearbook) to ones that are unique and that were developed specifically within this setting, such as the Male and Female Peer Mentorship Program. Debating, DECA, and the Robotics Club are effectively extensions of some of the academic programs. Others, such as the improv and drama clubs, are too, and expertly run by various specialty teachers. The Oral History Project enhances an already well-developed offering, bringing in opportunities to develop media skills, among other things.

The Oral History Project

“I try to approach history as something that helps you to understand the present,” says Scott Masters, a history teacher and founder of the school’s celebrated Oral History Project. “Whatever we’re confronting in the world right now, the answer is always in history, or at least there is some sort of parallel we can look to.” He quotes the idea (attributed to Mark Twain) that history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, but it always rhymes. “History for me is very much about giving you that kind of grounding in the world that we find ourselves in.”

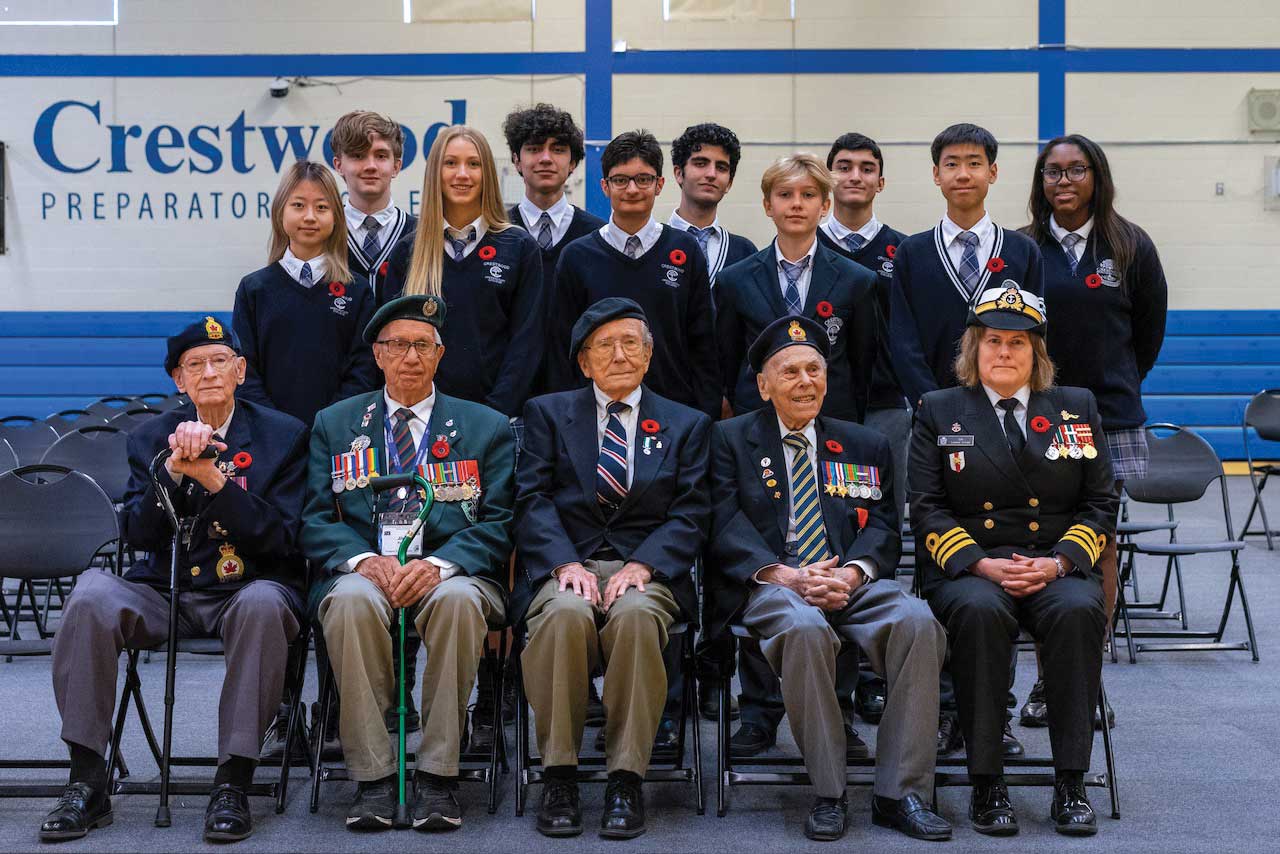

The core objectives of the Oral History Project are twofold. First, it’s an opportunity for students to learn history, actively, from the people who lived it. They are asked to approach essential topics through essential behaviours—learning about the past from the people who lived it, while also recording their voices and experiences so that they won’t be lost with time. Students are challenged to reach out to veterans and survivors, then to meet with them to probe and record their experience. “The basic premise,” says Masters, “is to get the students to talk to people who actually went through it. To get to know these people, to begin to see what you could call the emotional impact of history. It’s not just something you read in a book, but there are some pretty remarkable stories that they can dig into.” Second, it’s the creation of a one-of-a kind archive, one that gathers personal stories and makes them available to an online audience.

Part of the program’s success is that it doesn’t feel like busy work, homework, or a school project—participating students feel that they are contributing to a valuable and lasting archive, which, in truth, they absolutely are. It’s also a truly cross-disciplinary program, given that the tasks involved with research, archiving, and communication are so varied. “My son has done a lot with that,” says a parent. “Not so much on the actual history, but he’s done photography and video,” something that he’s rightly exceptionally proud of. Other students, including international students, can volunteer to translate interviews; and still others are tasked with prepping and incorporating audio, text, and photos into Crestwood’s Oral History Project webpage.

A wider story

The creation of the program is as good an example as you can get of how development is handled within the school, namely through granting teachers the freedom to follow their interests. In 2007, Scott Masters was awarded a Yad Vashem study grant to pursue Holocaust studies in Jerusalem. The project is a direct result of that experience, and was launched on his return. It has grown to include significant partnerships with local community organizations, including Sunnybrook Hospital’s Veterans Centre, Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, and the Noor Cultural Centre, all of which are close by. Says Masters, “I’ll take down a group of maybe 10 to 15 kids, to keep things small and manageable, and they will just sit around a table with World War II veterans—maybe three or four of them at a time—and delve into a whole bunch of questions. You know, learning about what it was like to grow up during the Depression, say, or why they enlisted. Some of the really gifted kids sort of learn to ask questions that are a little unique and off the beaten path. And we end up with this really fascinating day-in-the-life kind of thing.” It’s very intimate, and the connections are personal. “There’s almost a grandparent sort of connection. … And there are still important stories out there that need to be heard,” Masters adds. He gives a recent example of a wartime nurse at Sunnybrook who just turned 102, and who students interviewed for the project: “She still had really, really good recollection.” It’s hard to overstate how important that kind of experience can be for young people.

And on it goes, into areas and experiences that perhaps no one could have foreseen when Masters asked some students to interview a visiting veteran more than a decade ago. In the summer of 2017, Masters won a grant to participate in the Peace and Reconciliation Study Tour of Japan, China, and South Korea, interviewing survivors about their experiences in the war. That, and other initiatives, serve to broaden and enrich an already impressive program. The project has attracted teachers to the school who share the mindset and the passion for what it represents. “I first entered room 203 as a student teacher six years ago,” says Jason Hawkins, who has since become a full member of the staff. “Since that day, I have come to know Scott Masters as a mentor, a colleague, a department head, and as a friend. In each of these capacities, Scott has shown the same amazing level of skill that he does in his classroom practice. His love of history, and the work he puts into teaching it, has inspired me as a teacher and colleague.”

Living the lessons

Indeed, the more you know about the Oral History Project, the more compelling it becomes. It’s a great example of all the interdisciplinary descriptors that the world of education is rightly abuzz with these days: cross-disciplinary, multi-generational, multi-perspectival, multi-literate, cross-curricular. Students do all the interviewing, editing, translating, and digitizing. It cuts across a lot of areas of learning and collaboration. One of the things that’s so great about it, though, is that it wasn’t created as a means of offering all of those things, but rather to simply tell some important stories that desperately needed to be told. “Scott Masters lives what he teaches,” says Pagano. “We cannot expect more from an educator. … He has inspired young and old to understand and appreciate the connections between past and present, as well as those between endless sacrifice and eternal gratitude.”

One day when we visited, there was a curated display of World War II artifacts in the main hallway. Uniforms, medals, photographs—real things that tell a story, from real people who have a relationship with the school. Directly because of those relationships, Remembrance Day has grown to become perhaps the most important date in the school calendar, with the possible exception of graduation. Says Masters, “that grows right out of the history project, so whenever we do our Remembrance Day assembly, it’s not the typical thing that you would see at other schools. We’ve had 30 to 40 community members attend; 20 or so World War II vets attend. I don’t think there’s any other school in the country, maybe outside a military academy, that does that.” It’s a direct result of the relationships that have been fostered through the Oral History Project. “And the vets really like what they see is going on here; they bring their families. So I end up getting to know the next generation.” The event includes an annual veterans breakfast that parents rightly gush about. It’s a singular event, and one that clearly has a great traction within the school population and the community beyond. “I was amazed at how well it was organized and how they really honour the survivors and veterans,” a parent told us of her first experience with the event.

It’s a community event that, again, exemplifies the administration’s desire to find opportunities for the school to interact meaningfully and productively with the wider world. A visit to the Oral History Project website is recommended, both for what it is and also to give a sense of the kind of work being done within the school: www.crestwood.on.ca/ohp/. In addition, the “Crestwood Families” tab will grant a unique perspective on the diversity of the student body.

Student population/academic environment

“I love the texture and the look of the school now,” says Hecock. While there have been many renovations and improvements made to the structure during his tenure, it’s clear that he’s thinking more of the culture, the people, and how all interact within it. “It’s just a Crestwood culture,” says a student, echoing Hecock’s thoughts. “The way we relate to our teachers, to each other. … It’s just really accepting.”

One parent reports that, even up until a few years ago, the percentage of students arriving directly from the Lower School was as high as 60%. In recent years, however, that percentage has decreased somewhat, with a higher portion of students arriving from other schools and actively choosing Crestwood without any pre-association with it.

“I think this school has probably one of the most diverse student populations that you’ll see at any independent school in Toronto,” says Director of Admissions Kim Williams, a sentiment that is raised often in conversation with faculty. “It’s a true reflection of the community,” says a parent. “It’s a diverse community of children from all different backgrounds. … It’s a very open and warm environment.” The development of the elite athletics programs adds a number of layers to the student mix, which many see as an important benefit. “It’s a great thing in terms of what you see in the classroom,” says Masters, “and I think it’s a great thing in terms of how it readies the kids for what they’re going to see when they get out there in the world.” The students speak of diversity in the ways you might assume, but also more generally since, “there’s lots of different kinds of kids that come to this school,” bringing with them a broad range of interest and experience. The staff has been developed in a similar way. There are basketball notables, but there are three marathoners as well, all of whom have run the Boston Marathon. Arts interests, too, are well represented.

One thing that characterizes the student population, in our experience, is that the students all have clear ambitions—they all want to go places. “You’re choosing to be here,” says a student. “No one tells you you have to come here and pay tuition, but it comes with going to this school.… Coming here, you’re already under the assumption that you’re coming to better yourself academically, and put in the effort. And people here are used to that. It’s not something that you’re forced to do. … Everyone’s on the same page.” Adds another, “also what’s really nice is, I went to public school for Junior Kindergarten to Grade 6, and I was staying after school, but it wasn’t a thing—teachers weren’t available, they didn’t have to be available. … But that’s guaranteed here. Teachers are guaranteed to be open for help, so it’s not like you’re guessing, ‘are they going to be open? Is this actually going to happen?’, which is really nice.”

The students really see beyond the high school experience, and they have a good sense of the paths that they’ll follow afterward. They arrive each day from a wide catchment area, including as far afield as Brantford, Ajax, and the Beaches. They clearly choose the school for the fit and the sense of community, which is a good indication of the health of the program.

Parents and students report that the school is large enough to allow for a good range of curricular and extracurricular offerings, yet not so large that students feel lost in a crowd. “All the teachers know my name,” says a student. “Even if I don’t have them, they all know my name.” Says another student, “I think high school is as much about the experience as it is having the knowledge to go to the next level academically. It’s part of one’s life—make connections, have a good time—that’s part of what high school’s about.”

The proportion of international admissions has tripled in recent years, and the school works with homestay placement agencies to support that aspect of the student population. Those trends contribute to a school culture that actively and passively addresses diversity, including cultural, gender, and financial. “It’s not a snotty private school,” a parent told us. “It’s much more down to earth. There’s a little bit of everything. The spirit is down to earth.” Says a student when comparing Crestwood to his previous school, “here it’s a bit smaller, which is a good thing for me, because you get to know everybody really well. And class sizes are a bit smaller, so teachers are able to spread their attention out a bit more.”

Classes start at 8:45 a.m., with students able to gain access to the building as early as 6:45 a.m. Some apparently do arrive as early as that, which says something. “I get all my homework done in the morning,” a student told us, “because all the teachers who aren’t on duty are all open, and I can go in the class and get extra help. Which is really nice, because they’re always open.” Coming early and staying late is more the rule than the exception (“you can also come early just to hang out,” adds a student), which reflects the quality and breadth of the extracurricular offerings and the overall culture—no one’s counting the minutes, teachers and students alike. Breakfast is served in the cafeteria, which is run on a meal plan system or à la carte. Teachers start their tutorial and extra help offices at 8 a.m. each morning. At the end of the day, they make themselves available for questions and extra help.

Every second Wednesday, there’s a town hall (run by students) where everyone comes together. A house mentor system offers some opportunities to connect students and is done in consort with a teacher mentor. They meet several times throughout the school year, and the program is seen as an important catalyst for the school community. The device policy is typical: no phones in class or the hallways between classes, though they can be used in the cafeteria during lunch and before and after school.

When we asked students for ways they feel the school could be improved, there was a unanimous sense that wider halls might be nice. If the width of the hallways is the only gripe, as apparently it is, all is well.

Athletics

The basketball program, understandably, gets a lot of attention, though there is a broad athletic program, covering all the basics and then some. Lisa Newton has been with Crestwood since its second year and has seen the development of all levels of activity, from recreational to elite. “I’ve seen it from the bottom up,” she says. “We’ve definitely grown our program to be more competitive, but we’ve also made it more inclusive,” with levels of play for all students who wish to participate.

Interests that students bring forward are encouraged, as evidenced by a new ultimate frisbee league that was established at their instigation. A coach was interested in bringing curling in, so that was added as well. Says Newton, “we’re willing to try anything, and to offer whatever program the kids are interested in. If there’s enough interest, we’ll do it.” She feels, as do others, that the integration of the elite basketball, hockey, and soccer programs benefits the entire student body. “I think there’s a lot to be learned from playing with elite-level players about heart, about drive, hard work. For kids that are elite that are playing with kids who maybe aren’t at quite a high level, there’s a lot to be learned there as well—how to be a good leader, how to support other people. There are so many lessons that they are learning.”

Every team is built from an open tryout, from Grade 7 up, rather than a house-league style program where everyone who wishes to sign up does. Bigger rosters are maintained in the younger grades in order to involve as many players as possible. If necessary, they’ll add a second competitive team in order to accommodate them. Cuts may be made if students’ grades are falling or if they display bad attitudes or start skipping classes, but for the most part, these situations are rare. The focus, says Newton, is on making good memories and good relationships, and on encouraging relationships that may not naturally arise in other settings.

There is a cardio room and a weight training room, and fitness and conditioning coaches come every Tuesday and Thursday. They predominantly work with the basketball program, though time is also set aside to work with other athletes. Students are free to use the weight room outside of class time. There are intramurals at lunch for four out of every eight days in the cycle. In all, it’s a well-rounded program. Parents and students confirm that, while not everyone plays on the varsity teams, there is ample opportunity for involvement. Though the strength of the program, in terms of wins, is considerable, there’s a good effort to make sure that students see the personal benefits of participation first. “It’s a good experience, even just as a teenager growing up,” a student told us. “One should have that experience of bonding with a team, going through the ups and downs of that team relationship, holding each other accountable.”

The success of the varsity teams promotes a greater involvement, given that the rewards of physical activity—belonging, feeling part of a team, etc.—are more apparent here than at other schools of the same stature and size. The intention is to take the model and apply it to both hockey and soccer, and certainly significant steps have been taken in that regard. If there’s a downside, it’s that the high visibility of the athletics program could outshine core academic excellence. Certainly, that risk is clear, both in the school and out. Parents note that when elite athletes earn a scholarship to a top-tier post-secondary institution, the school celebrates with an assembly, though students gaining awards to academic programs don’t get the same treatment. It’s easy to understand why, though it can risk becoming a slippery slope. The challenge for Crestwood moving forward is to ensure that it’s not seen only as a sports school, something that a student noted to us that he felt was a growing misconception. It isn’t, and doesn’t intend to be.

The elite basketball program

Marlo Davis is a very familiar name in Canadian high school basketball as he enters his eight season as head coach of the prestigious Crestwood Preparatory College women’s basketball team. Davis also serves as the program director and assistant coach with the men’s program. During his time at Crestwood, Davis has led the women to three provincial championships and he has guided over 20 student-athletes to achieve their dreams of playing NCAA basketball.

Internationally, Davis has been an assistant coach with the Canadian U19 Junior National Team for four years, where he most recently helped the team to a bronze medal at the 2023 U19 Women’s World Cup. Davis has also been an assistant coach with the Niagara River Lions of the Canadian Elite Basketball League for two seasons, where he helped the team finish with the best overall record in 2023.

Elijah Fisher was in the first cohort, arriving at age 13 and already a distinguished athlete. Some believe he may become the best basketball player the country has ever produced. Shayeann Day-Wilson was in that cohort as well. When she was only 15, she had already received offers from more than 70 Division I universities in the US.“ At my last school, they didn’t really care about me,” says Fisher. “They just put me in the system and said I can’t do this and that. Now, to get the opportunity to come here, teachers look at me differently and show me that I can actually do the work. They’ve helped me take my education even higher, to really strive for it.” An expressed intention of the elite programs is to give the athletes exposure to U Sports and NCAA. In the 2018/19 academic year, the school hosted more than 50 NCAA coaches, and regularly sent players out to US and Canadian tournaments where they know there will be scouts present.

“This was a great opportunity, especially where we are from,” says Rose Day, Shayeann Day-Wilson’s mother. “So I said, ‘Right on.’ … I don’t want her to go to a school where her basketball comes first”—a sentiment that is echoed throughout the parent population, including, like Day, parents of athletes. It’s a balancing act, to be sure, and one that the administration is, to their credit, very keen to get right. Says Newton, “Crestwood is an academic institution, and we’ve always been an academic institution for 40 years. So, we’re going to give these kids, through basketball, a way to come to a high-end private school.”

Wellness

Faculty describe the school as happy and supportive, something that the parents we spoke with all seconded. There is a concerted effort to promote inclusivity, from the postings on the doors, to more substantive initiatives, including ongoing professional development intended to ensure that faculty have the tools and the perspectives to ensure that the student experience is inclusive and egalitarian. The focus on values, too, is often raised in conversation with faculty and parents, and it contributes significantly to the students’ daily experience of the school. Pagano’s goal of “happy, productive kids that come to school each day knowing that it’s going to be a good day” is supported through a range of tangible initiatives. “It was always viewed as an alternative to schools that added pressure and stress,” says Jeff Mitz, former head of the guidance department. “This was a place where there was a lot of nurturing support, caring staff, particularly for students that needed an arm around their shoulders. This was a great place for them.”

There are three full-time counsellors within the guidance department, and together they provide university counselling and emotional and social support to the entire student body. All students are required to meet with the guidance staff at intervals throughout the school year and, by all reports, contact is close and frequent. Guidance staff regularly check in with homerooms, making sure that students are aware of the support structures available to them. They are approached individually, though there is an open-door policy as well, and students are encouraged to approach the staff of their own volition. Some students have designated peer mentors. In Grades 7 through 10, the contact is typically centred on social/emotional issues, with some discussion of aspirations. University counselling begins in earnest in Grade 11 and includes the usual battery of interest testing (including introspective self-reporting, as with the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator) and career inventories. When asked specifically about the university counselling piece, a parent said, “I think it’s very good. … I actually have a meeting with one of the counsellors on Thursday.” She notes that she received an email inviting her to come in, something that she appreciated: being involved, and also being proactively invited to be involved. Students in our experience are amiable and respectful with each other, and the same with faculty and staff. From time to time, there are disciplinary issues in any high school environment, and certainly Crestwood isn’t immune. The approach to discipline is kept very much in line with Pagano’s desire to work empathetically with students, to begin from a place of discussion, to offer care, and to appeal first to each student’s better nature. Parents report that discipline is applied swiftly and sympathetically, and that students are told early and often of what kinds of behaviours are expected of them. Rather than lecturing students that bullying won’t be tolerated (it won’t), the faculty is more proactive, ensuring that empathetic behaviour is actively promoted as the norm, and that patterns and protocols for reporting are clear and well communicated.

Parents and alumni

Parents describe the administration and faculty as approachable, either in person or through email and digital messaging. Parents say access to staff is excellent, with problems always sorted out quickly and efficiently. The school uses Edsby, a management app that allows students and teachers to track timetables and exam schedules, activities, announcements, and school news. Teachers include information there regarding student progress, as well as any issues that may present themselves outside of the more regular progress reports.

By all accounts, there is a range of opportunities for parents to play an active role within the school. The parent council is active and engaged, very much on a first-name basis with administration and faculty. Parents report that there are ample opportunities to be involved directly in the school, both formally and informally. “It’s very much how little or how much you want to be involved,” one told us, noting that parents feel welcome to volunteer, though they don’t feel pressured to contribute.

Getting in

Entry is based on assessments and interviews, and the application process is what you’d expect for a school of this size, stature, focus, and location. The application deadline is in February for enrollment the following September. Applicants are asked to sit an entrance exam (assessing literacy and numeracy) prior to the application deadline. Dates are posted on the school website, and the exam is invigilated in person, on location at the school, with some accommodation available for international students. Interviews, too, are scheduled prior to the application deadline. Otherwise, the application package requires all the documentation that you’d expect it might, including relevant transcripts and recent report cards.

The process is intentionally transparent, intending to create a level playing field for applicants of all backgrounds and circumstances. Interviews can seem daunting, though parents and students report that the experience was more like a chat with friends. The school rightly sees the relationship they have with each student as precisely that—a relationship—and it has to be right, collegial, and comfortable for all involved. The application process is handled very much with that goal in mind. Many students arrive from the Lower School program, though no preference is given in that regard, and it certainly isn’t a prerequisite to entrance into the Upper School.

Money matters

The fees are what you’d expect for a school of this size, focus, and location. That said, for parents the question is less about cost than value. “The reason [we chose Crestwood] was that I knew he could do better,” a current parent told us. “The biggest difference for me is that, at public school, you’d go in to talk with a teacher and they’d say, ‘little Johnny’s not doing well in English. What are you going to do about it?’ At Crestwood, it’s a different conversation. They say, ‘little Johnny’s not doing well in English. Here’s an approach I’d like to take. What do you think?’” She continues, “They don’t look to you to solve it. [Instead,] they share the responsibility for your child’s success.”

It’s an investment, to be sure, and one that most families don’t take lightly. For the students that attend, the value of Crestwood is seen in the opportunities it provides, the individual supports offered, and the focus on preparation for post-secondary studies. “That academic success and esteem,” says a parent, “that’s what’s going to get him into the next school.”

The takeaway

Truly, there is no school in the country that shares Crestwood’s profile, and there are lots of good reasons for that. Faculty are spirited, engaged, and open to new ideas and new approaches to the extent that they will deliver a richer experience, and a wider range of transferrable skills.

Since the beginning, the school’s reputation is based in its ability to address each student’s individual learning, and adapting the material to various styles of learning. “Crestwood has a really strong history of being able to educate students with a range of different exceptionalities, and different personalities,” says Esther Lee, something that drew her to the school. Hecock says that, as a school, “it is your job to explore what they can really do” academically, helping them reach their potential and reach toward their personal aspirations in school and beyond. There is a rich program of extracurriculars, though the focus is on academics, including the development of sound study and test-taking skills. The Maximizing Academic Performance Program begins in the Lower School and augments a traditional approach to education, one that is didactic and where assessment is objective. The Oral History Project rates very highly as well, and it’s indicative of the school’s integrated approach to learning and program development.

The culture at Crestwood, as one parent noted, is attractively down to earth—neither quirky nor elitist, but instead dignified, respectful, and comfortable. While values have long been a priority within the school, recent initiatives have brought character education more tangibly to the fore, as is evidenced throughout the school. “Getting everyone involved is a really big thing at Crestwood,” says a student. “They really want you to be a part of the school.” High rates of extracurricular participation bear that out.

The ideal students are those who have their sights set clearly on success within a university career, are motivated toward that goal, and are seeking to increase or improve their academic prospects. That the guiding principle is to provide a place where staff and students can be happy, empowered, and productive should put prospective parents at ease—the program is preparatory, but not at the expense of well-being and a rich high school experience.