Académie Westboro Academy THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Académie Westboro Academy, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

“We’re intentionally small, and we’re proud of it,” says past head of school Meg Garrard. “We shout it from the rooftops. This is part of what makes us great.”

I reached Garrard by phone during the darkest days of the pandemic. The new head, Elyane Ruel, had been announced, but when I began asking about the history, the culture of the school, and the capital development over the years, the feeling was unanimous: “You have to talk to Meg.” At the time she was in the midst of moving on to other things, having served two terms as head of the school during which she presided over some significant advancements, including a move to the current property. She had left a lasting mark on the culture of Westboro, and while not the first or even the second head, the feeling is that her leadership really brought the school into its own. Maybe in part because of all that, she felt that the time had come. She was leaving to make way for new leadership, with new insights and new energy.

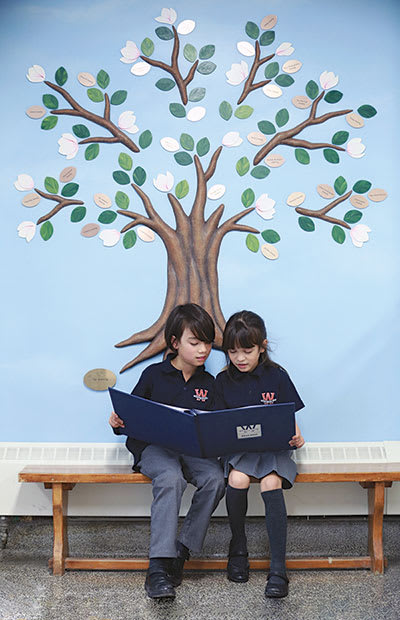

One thing that wouldn’t change, she was clear, was size. Garrard’s sentiment—being small is a strength—is shared by the staff and the students. Indeed, it’s typically the first thing anyone says when asked about what they love about the school. At 170 students, it’s not tiny. The school offers only the primary and elementary levels, so there is an average of 17 students in each grade. That’s a nice, comfortable size to allow for a sense of bustle within the hallways and lively conversations in class. But it’s not so large that kids can easily get lost in the crowd or hide away at the back of the room. “Everyone seems to know everyone,” says teacher Caitlin Cadeau. “The older kids pass by the little kids in the hallway and know them by name. It’s, you know, ‘How are you doing, I know that you had your tournament,’ or this or that. It feels like a family. You’re not lost in a sea of people. … that’s something I think that we continue to do really well. To make everyone feel that they’re seen and heard.” There’s a familiarity between the students and faculty, with students getting to know their teachers over the course of years, rather than always having one teacher one year and another the next. Says one student, “If you are struggling in a certain subject or having a hard time understanding a lesson, you can always feel free to email the teachers or reach out to them in person” even if they aren’t your current teacher, or even teaching in your current grade.

To those outside the school, however, the most defining feature isn’t the size but the language program. “One of the number one questions parents ask me,” says Chantale Bessette, director of admissions, “is about the difference between French immersion and bilingual schools.” The terminology is somewhat fluid, but Westboro isn’t an immersion school in the way that most people have come to know the term, namely, the way it has been described within the public school system. French immersion programs were first offered in Canadian public schools in the 1970s following a concept as outlined in the Official Languages Act. It was a product of Pierre Trudeau’s vision for a bilingual nation and was funded through the provisions made within the Act. Notably, it was intended for English speaking students for whom French is a second language, and (let’s be honest about this) for whom it would always be a second or secondary language.

Fifty years and a few generations later, the success of public school immersion programs is debatable. Not only is the nation not more functionally bilingual today that it was then but immersion schools themselves aren’t functionally bilingual either. French is offered in class but isn’t typically used in any meaningful way beyond that. Assemblies, field trips, guest speakers, announcements, signage and posters, and conversation in the hallways are in English. Disconcertingly, within public immersion schools there is no formal requirement for teachers to be native French speakers. Quite often, they aren’t. In those environments, students gain exposure to the language, which has value, but few if any students graduate from public language programs truly bilingual or having had any meaningful experience of francophone culture.

When parents ask Bessette about the difference between an immersion program and a bilingual school (which is how Westboro defines itself) those are the things that they are thinking about. The parents that turn to Westboro are looking to grant their children something more than merely a passing acquaintance with French. Rather, they want their children to be functionally bilingual in the fullest sense of that term.

And that, ultimately, is what Westboro was created to offer. Both languages are instructional languages. All instructors offering courses in French are required to be native French speakers. Westboro doesn’t specifically require that all teachers be bilingual, yet most are comfortable in both languages, even if they aren’t teaching in French, to the extent that they are apt to switch between both during conversations in the hallway or in the staff areas. Also unlike public immersion schools, Westboro enrols both anglophone and francophone students; kids arriving from French language households would just as easily find a place within the school as those arriving from English speaking households. (Given the location of the school within one of the most bilingual cities in the nation, there are students arriving from mixed households where one parent is anglophone and the other is francophone.)

Following on, the academic and social environment at the school is purposefully crafted to be bilingual in the truest sense, something that’s apparent even just stepping in the front door. The office administrator greets visitors, students, and staff in French. In the hallways, both languages are spoken, with teachers subtly reinforcing that by speaking to students in French, at times switching mid-stream between languages. “If you go to the office and you want a band aid,” says Garrard, “you have to do it in French.” There are French field trips. The day I visited I arrived a bit early and took a seat in the staff lounge just off the main foyer. All the conversation there was in French, from “Good morning,” to “How fresh is this coffee,” to “Who’s that guy sitting over there?” When homeroom classes convened, a student gave the morning announcements over the intercom in French, something that occurs half the time. And on it went.

Ultimately, the answer to the question that Bessette is frequently asked—about how immersion differs from bilingual education—is all of that: environment, culture, relationships, authenticity, intent, and lived experience. The intentions of the Westboro language program are to provide authentic learning: to offer students an intensive and meaningful engagement within linguistic and cultural traditions; to increase employability; to develop the ability communicate effectively to a variety of people and in a variety of settings; and to enhance cognitive development. There is also a clear understanding that it’s not just about grammar and vocabulary, but the lives people live, the way that they engage with the people and communities that they move through. In lessons, as well as chat between classes, francophone teachers use examples from their lives and therefore provide a window onto the larger world of the language they are speaking. “It’s a space,” says Derek Rhodenizer, director of academics, “this is a space that is actually bilingual.”

The results are equally clear. As alumni and families invariably report, the students leave after Grade 8 fluent in both languages and then some. (One teacher admitted to us that “in my first year of teaching here, I wasn’t sold on that, but within a couple of years I couldn’t believe how the kids could speak French.”) They have had authentic experiences with both the cultures and cultural traditions, having gained friends and mentors from both linguistic heritages. They also personally identify as bilingual. Speaking with the graduating students, you see that they’re proud of that, and are buoyed by what they’ve attained. From writing poetry, to taking part in the robotics program, to visiting a museum during a field trip, they communicate in both of the nation’s official languages. Bessette noted at one point that she feels the definition of bilingualism is when people dream in both languages and that it’s that level of fluency that the school strives to achieve and, by all reports, it succeeds. (To test the idea I asked some students if they ever dream in French. There were lots of smiles and yeses all around.)

Key words for Académie Westboro Academy: Values. Care. Community.

Basics and background

Académie Westboro Academy is a coed, non-denominational day school offering the Ontario and Quebec provincial curricula for students in Junior Kindergarten through Grade 8. It delivers a liberal arts education, with equal weight given to the arts, sciences, and humanities. As far as the overall project, “we’re looking to build good citizens,” says Garrard. “I know that sounds too simplified,” she quickly adds, “but basically we’re trying to help kids develop the skills they need to be thoughtful, engaged people that you might want as your friend or your co-worker down the road.” All of that—the goal as well as the apology that it sounds simple—is telling of the overall school culture. There has never been a desire to be overly grand in the way that some schools are. There isn’t ivy on the exterior walls, or priceless art lining the hallways. Rather, this is a place for young people to grow into good friends and neighbours, and it has been crafted with their needs foremost in mind.

Founded in 1993, Westboro is currently at its third location, a leased property in south Ottawa set within a residential neighbourhood southwest of the intersection of Bank and Heron streets. The property abuts Kaladar Park and shares a sports field with École élémentaire catholique d’enseignement personnalisé Lamoureux, a Catholic public school. Given the location—tucked away, accessed via secondary streets—this isn’t a school you just happen across, but one that you only arrive at intentionally. Indeed, that was one of the attractions of the property. The street out front is sleepy and lightly trafficked, so morning drop offs are calm and unhurried, with parents able to pull up and pause.

The school yard is open and supervised a half hour prior to the start of the formal school day. There are no school buses, so drop offs are done by parents, who welcome the flexibility that the supervised half hour allows. They also tend to linger a bit. It’s less “drop off” than “drop in,” with parents visible in the school yard, finding a moment to chat with other parents and teachers before they go off to start their work days. It’s not uncommon to see them still chatting there even after the students have gone into the school. That kind of interaction happens at the end of the day as well, and certainly there’s no pressure to move on.

The property isn’t sprawling, though the spaces are well appointed. The play space out back, known generally as Yard One, serves for the younger students while the older ones, those in Grades 4 and up, gravitate to the shared sports field—Yard Two—on the adjacent property. Included there is a large, well-groomed athletics field (Westboro has exclusive use of it during the school day) and a park with picnic benches in the shade of some mature trees. There’s a creek nearby. Those things—the fields, the location, the green space to the south—grant a character to the property that is a welcome contrast to the denser, more bustling areas of the city to the north.

“It was very grassroots,” says Meg Garrard of the earliest days of the school. “They were building desks and, literally, building the school.” The “they” in this case were parents. It was the early nineties and they had gathered together to create a new school. “It was super hands-on. Classic church basement,” she says. “The whole bit.” In many cases the parents paid for materials and supplies out of their own pockets, in the assumption that they’d be paid back later, which they were.

Not all schools start that way, but some of the best ones do; they start as an idea, the desire to fill a need, to be an expression of a specific community. In this instance, most of the families had daughters attending Joan of Arc, a girls-only school, and they wanted a similar school for their sons. Like Joan of Arc, it would be independent, so that while it would teach to the provincial curriculum, families would have a say in how the curriculum was delivered. The staff would be agile, keen to try new things in order to inspire learners. Most importantly, it would be bilingual. Also like Joan of Arc, it would sit under the umbrella of Catholic education yet be free to chart its own course in that regard. Unlike Joan of Arc, it would be coed. (In an unlikely bit of trivia, the building that Westboro now occupies is identical to the one that Joan of Arc occupies. Both were once owned by the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, and both built to the same blueprints.)

And so it was. In the fall of that year, Académie Westboro Academy began with just six Grade 1 boys. It was named Westboro after the area of the city that the school sat within at that time, though it’s moved twice in the years since, and is nowhere near Westboro today. (“So, yeah,” deadpans Garrard, “if you ever encounter anyone who is thinking about founding a school, I would recommend that they not name it after the neighbourhood that the church basement is in.”) The student body grew, quickly reaching the enrolment level that it maintains today. As a result, it’s been this size—about 170 students—throughout the majority of its life. The second location was in a shared building that was literally surrounded by a massive city park. The faculty loved the park but were less sold on the building itself. “We were stuffed in there—we didn’t have a gym. It was never meant to be a school.” So, in 2018, the school moved to the present location. This one feels like home, as if the school has arrived at the destination it’s been heading for, and growing toward, since it was founded three decades ago.

Leadership

Head of School Elyane Ruel, hired in 2020, arrived with professional attributes and personal experiences that are exceptionally well aligned with the history and the values of the school. She was raised in a bilingual household and is conversant in French and English, as well as with the cultures that the languages represent. The school isn’t an international school per se, though it nevertheless promotes an international gaze, and that was a box that Ruel also very firmly checked. Her first teaching position was in an Inuit school and she then went on to teaching and administrative positions at six international schools in six different countries, including those in Bolivia and Romania.

Ruel is forward looking, easy to talk to, and, in a world of lots of big, expansive ideas of what education can be, she’s also refreshingly level headed. When asked what she feels the program can best offer students, her thoughts first turn to the basics. Things like “an ability to write legibly and to compose a text that makes sense, without having to read it aloud to decode how you might have wanted it to read.” She feels students should learn what it means to offer an informed opinion, as distinct from just an opinion. “Some schools say ‘well let’s just have them discuss it.’ But if they’re only discussing their opinion, then it doesn’t hold much value. You need to have researched it so you’re discussing from an informed perspective. … I’m not fixed to a specific core set of basic knowledge, but I do think you need to know enough about something to be able to talk about it in a knowledgeable way.”

She feels the same about math. “I get frustrated with schools that claim to be more progressive in their math teaching, but if you ask a Grade 8 student what’s seven times seven, they can show you twelve different ways to get to the answer, but they can’t tell you it’s 49.” And, again, she’s clear that it’s not one or the other, and that the best schools do both. “You also need that space for creative thinking and collaboration,” she says, but “there’s also a time for that knowledge base.” Sitting in her office, looking out the windows at the students arriving for the day, you feel like you’re in very good hands.

When I ask her what she feels makes a good school great, she say that it’s an ability to put students first. For her a great school is one where teachers are able and inclined to work together with the students’ best interests in mind. It’s one “where everyone in the community has a voice, and the systems are in place to adapt to what’s needed.” She feels that there are no mysteries in how those environments are encouraged. “A lot of it has to do simply with how you treat each other. I think one of the things that makes this school great is that teachers have a certain amount of professional freedom because we treat them as professionals who know what they’re doing.”

I ask her what she feels the hiring committee saw in her. She says that it was probably the things that first come to mind: bilingualism and biculturalism. “It’s one thing to speak two languages, and it’s another to get the cultural differences between them.” She doesn’t mention it, but she also projects a sense of groundedness and confidence in what education is about and what she’s worked throughout her career to bring to the various educational settings she’s worked within. After a pause she adds, “And the fact that I spent so much time in private schools. So I get the tensions and the realities. Knowing that we are a private school, so we serve parents in a different way, but that we also have to stand true to our educational values.”

As she talks about the hiring process a smile creeps onto her face. “It was an incredibly interesting process, and not one that I’ve experienced before.” Typically, hiring starts with lots of different people interviewing the candidate, often one-on-one and then leading to a panel interview. They want to know what you’ve got, what you can bring in terms of credentials and experience. Here, she says, they flipped it. “I was given the opportunity to interview lots of different people. They weren’t asking me anything. [Instead] it was ‘find out what you want to know about the school.’” There was ultimately a panel interview, “but they asked me to start with a short presentation on ‘What have you learned about the school, what is its strength, and what might be the next steps you would take?’ ” On one level, she admits that it was a bit daunting. If she hadn’t known what to ask all those people in the days prior, then she wouldn’t have known what to present. Though, of course, that was probably the point. “What I identified as the school strength was basically the hedgehog concept,” an analogy that comes from the writing of researcher and author Jim Collins. The idea is that the hedgehog only does one thing when it’s under threat—it rolls up in a ball—but it does it extremely well. Says Ruel, “It’s about recognizing what you do well, and then do it well, and don’t try to do ten thousand other things.” To the panel she said, “You are a bilingual school, that’s what you do well, and that’s how you define yourself.” They agreed. And for next steps? “I said that accreditation with CAIS [the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools] might be something to look into.” And they are. From there, she turned to the strategic plan and the need coming out of the pandemic to rededicate the school to the value, the community, and the direction that the plan outlines for the next five years.

It’s hard to overestimate what all of that says both about Ruel and the school itself. For one, the organizational structure is sound, strong, yet also notably flat. The panel asked for Ruel’s expertise, looking to learn about her strengths rather than probing for weaknesses or areas where she might fall short. The questions they asked were honest. When it came time to ask where she felt the school should be heading, she feels that it wasn’t a test, and there wasn’t an answer they were looking for. Instead, they genuinely wanted to know what she thought based on her personal experience and expertise. In our experience of Westboro, that kind of relationship is an analogue for those that exist at all levels within the school, such as between parents and staff, students and teachers, and teachers and administration.

While it’s still early days, that’s how she’s gone about the task she was given. “One of the things I started to do when I arrived at this school was to identify what the white noise is.” Things like printers that don’t work, conflicts within schedules, and so on. “What are all the things that are just taking up time, sucking energy, and have nothing to do with learning but have become elements of frustration. It’s finding those things. The things that take intellectual and emotional energy [and] that tie in with wellness.” She recalls a school where she worked where the bell system was causing trouble. The bells were going off at the wrong times, or sometimes not at all. It was causing confusion and stress, “and finally somebody says, ‘Why don’t we just get rid of the bells? Why don’t we just get a whistle?’ ” As so they did. One good idea, a quick execution, “and all the stress was gone.”

She laughs at the simplicity of it, but also the lesson it teaches. To capitalize on that kind of innate agility—to fire in, to see what’s working and what isn’t, to act quickly—is what Ruel believes private schooling is particularly well positioned to deliver. “What is getting in your way? What is provoking you? And if it’s not serving student learning, then it’s not doing any good, so let’s change and restructure.” Or buy a whistle. “As a private school there are pressure points that we don’t have to follow. When you’re dealing with huge school boards, you might have to make decisions that you might not necessarily make if you had the flexibility of a smaller school.”

This is Ruel’s eighth private school, so she’s seen a lot. She notes that she has never known a school “where the teachers care so much about their school. I’ve inherited a team that truly loves the school. People feel like they belong.” Happily, she admits that she came to Westboro at a particularly strong point in its life, including stable governance and solid financial foundation. “It’s well set up,” she says, crediting the leadership of her predecessor. “Things just work.”

Her vision for the future includes the creation of more diversity within the student body and more connections with the community at large. Per the hedgehog principle, she intends to remain true to what the school has done well: bilingual education, strong leadership, and wellness. “But diversity is a big one,” she says. I ask her to imagine what, years from now, she hopes people will remember of her time at Westboro. She answers without a pause. “That I was part of a team that worked together creating a space where everyone felt that they were comfortable to learn. And that I always put the students first.”

Academics

The academic program is challenging yet supportive, demanding without being onerous. The faculty are keen to innovate and adopt new best practices, though this isn’t a school that is quick to deny the value of the tried and true. In speaking of traditional versus progressive academic delivery, Ruel feels that “schools make the mistake of having to stand on the pinnacle of one or the other” rather than seeing the value in both. She uses herself as an example, having come through secondary 4 in Quebec (the equivalent of Grade 11 in Ontario) at a time when Latin was still taught. “It’s one of the best things I ever learned,” she says. “Every time I come across a word I don’t know, I just break it down to the roots. I’m not saying we’re going to teach that here, but I think that there are elements of a more classical approach that really serve a purpose.”

Derek Rhodenizer, director of academics, agrees. “I wouldn’t call us as traditional as some other schools,” says Rhodenizer. But “we do have homework, for example. This is not a homework-free zone.” He adds, exaggerating the point, “drill and kill is not lost on me and I see the importance of that.” Echoing Ruel’s thoughts, he adds, “That is one of the things that occasionally gets thrown out, you know, the baby goes with the bathwater. … Discovery math is very good, but if your basics and foundations aren’t there, it can make it tough to fluidly navigate higher-order concepts.” Similarly, one of the Grade 8 students I spoke with had taken a grammar test that morning, one reviewing French adjective and verbs. At some schools, that would be unusual, and too often grammar—parsing sentences, knowing the parts of speech—is seen as outdated, perhaps a bit musty. Here, the value is understood and the benefits are clear: the students gain a sense of mastery over the material and gain the basis necessary to move on to meaningful application of the core concepts.

Rhodenizer is exceptionally easy to talk to, which is likely why he is so good in his role. He’s delightfully honest—most people in his role likely wouldn’t voice, for example, that drilling verbs or times tables isn’t necessarily a bad thing. He’s also keen to think hard about where he can add value while remaining cautious, particularly around the buzzwords that attend to many private and independent schools. When I mention curriculum development, he is wary, noting that “curriculum” is a word that can mean very different things to different people. He underscores the fact that the curriculum proper—the topic sequencing and student outcomes—is decided by the province.

Everything else—how the curriculum is delivered, pacing—is decided by the school and is the added value that he feels faculty are responsible for bringing to the learning. “One of the angles that I really push hard on,” he says, “is the ‘And then what?’ Meaning, yes, you have the basics in hand, have developed a mastery with the core learning. Great. Now, what are you going to do with it? How are you going to apply it?” For him, the answers aren’t as obvious as some might think, and he encourages faculty to be creative, something I saw ample examples of. In one instance, the students talked with delight about how math teacher Zachary Brain used an analysis of sports statistics as a way into the concepts of median and mean. They then followed a team’s progress through the sporting season, using statistics to make predictions of future outcomes. The students were jazzed just thinking about it.

There is also a welcome belief in letting the students take their time. Says Rhodenizer, “I see other schools say, ‘We do the Grade 8 curriculum and then some.’ I’d rather have [students] do the Grade 8 curriculum really, really well. Do it so well that they really deeply understand everything within it. I don’t need you to skip to Grade 9. That’s for Grade 9.” In a world where many in his role would shy from saying something like that, it’s refreshing that he is so open.

French is taught as a first language using the Quebec French curriculum—it is exactly the French language and literature curriculum that students in Quebec are using—so the emphasis on writing and grammar is quite different from that in immersion settings. This isn’t English curriculum in translation; were a student from Westboro to sit in with peers in a French literature class in Quebec, they’d know the context, the material, and the issues being discussed and could easily jump in and take part.

Junior and Senior Kindergarten is French all day in order to give the kids a good head start with the language, and also to reinforce the idea that, here, they’ll be speaking French for much of the day. “At that age I find they are like little sponges,” says Janick Lauzon, who has been a junior kindergarten teacher with the school for 19 years. “They pick up very, very quickly.”

The teachers are clearly dedicated to the overall project of the school and share a sense of ownership for it, something that is evident in a variety of ways. On the day I visited, I met three teachers who had been with the school for two decades, which is telling, given that the faculty is only about twenty members or so. Zachary Brain, a recent hire, admits that he was surprised by the amount of time that many of the teachers have been with the school. “That teachers have been here for two decades is unheard of. The fact that people just want to stay within this environment says a lot about it.” Nathalie Poirier, a Grade 7 and Grade 8 French and Social Studies teacher who has been on staff since 2001, says that “for me, of course it’s my job, but I really care what happens to this school. And I think that shows in everything that we do.”

The teachers bring a broad range of international experience; certainly more than you’d expect in a faculty of this size. Three have taught at communities in the far north—Nathalie Poirier, Karin Stenman, and Elayne Ruel—and others have taught internationally, including Zachary Brain, Alison Strang, Marc Lebeau, and Derek Rhodenizer. Brenda Dunlop has taught at international schools in Colombia and Kuwait. Janick Lauzon has participated in numerous humanitarian projects in Mexico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Kenya, and Ecuador, and has organized student trips to Ecuador. It’s not essential that a school have that level of international experience within its staff, perhaps particularly at this level, but it’s a benefit all the same. For one, these are teachers who themselves are somewhat adventurous, who are willing and able to reach out into the world and follow their own path through it. That’s reflected in their teaching, particularly given the latitude that they’re granted within their classrooms. “I’ve never been in a teaching environment that has been this free, and that works this well,” says Zachary Brain, who taught in four schools in the United States prior to arriving at Westboro. “There are no handcuffs … and that’s because of the trust that goes all round. The families’ trust in us, but also the administration.” Says another, “we could be teaching in the public system, with the big pension, but we choose to stay here.” The culture and the freedom are the reasons that she and others cite for that decision. “Truly, my intention wasn’t to stay for very long,” says Poirier, “and 22 years later, I’m still here. There are reasons for that.” “The students like to be here because we like to be here,” adds Brain. “It wouldn’t work if we weren’t happy.”

Academic environment

The faculty meets regularly throughout the year to review student success, and professional development is detailed and ongoing. When I met with Derek Rhodenizer the school was five years into an initiative to innovate new teaching strategies and approaches. Part of that included bringing in experts, either in person or remotely, to address staff and workshop new ideas. (He chuckles, thinking of his idea four years ago to conference digitally. Now, of course, that’s anything but an innovative idea.) Development initiatives take their cues from the teachers themselves, and Rhodenizer uses the example of spiralling the math curriculum. They wanted to bring that concept on board, so he reached out to national experts, having them conference with the math teachers. “We’re an independent school, so we’re isolated,” he says, meaning that the school doesn’t have the benefit of collegiality that a public one might, given that it sits within a larger school board. On the flipside, as he’s well aware, that independence brings agility and freedom: he’s able to source consultants and expertise from across the country, even around the world, and he does. Some development workshops are school-wide—he mentions one a few years ago addressing reconciliation—though more typically they are run within departments or, at times, one-on-one.

Rhodenizer also works overtly to address all aspects of teaching, not only the formal nuts and bolts of the curriculum or delivery. “We had pineapple day,” he says, the pineapple being an international symbol of welcome. On that day sat in on their colleagues’ lessons to get a sense of their teaching styles and techniques. “We don’t normally get a chance to do that. So having the Grade 8 teacher go sit in the kindergarten class and watch them teach was a pretty cool opportunity to glean things that you might not otherwise glean.” He tend to talks about these as “little things,” though they aren’t, and when pressed he admits that, yes, they are bigger than they may appear. Taken together, all those “little things” contribute to a culture of the school and the strength of the offering.

As does language. It would be hard to function here without switching between languages. I don’t speak French fluently, and during the visit, I regretted that almost continually, at every step feeling like I was missing out on something. At one point during the tour a teacher was speaking very animatedly to two elementary students in the playground during recess, sharing a good laugh, though because they were speaking French, I wasn’t’ able to share in the fun. The students switch back and forth depending on who they’re talking with, whatever they are trying to say or, perhaps, for no real reason at all beyond, simply, because they can.

Student population

When I ask the students “Who are you? What is a Westboro student?” the first answer given is “We’re always there for one another.” That’s followed by lots of nods from the others around the circle. (We met beneath a marquee outside for the sake of social distancing.) “School-work-wise, if anyone is having trouble, other people are there for you,” says another, and he means that in terms of both teachers and peers. Many of the students come to know each other outside of the school day. “You kind of know everybody,” says another, “and so you’re never kind of left out. Everyone has different likes, but there’s stuff you have in common, so you’re always included.”

Whether they arrive this way or if it’s something they develop within their time at Westboro, the students tend to be outgoing while thoughtful, eager to speak up while not given to dominating a discussion. One student I met in the hallway is very intellectually able, operating above her peer group, though with a unique learning profile. She engaged well with others and was as much an integral part of the community as anyone else. Later, Bessette noted that her parents were cautious when first coming to the school, given their prior experience at other schools, and have been exceptionally pleased with their experience. Bessette feels that’s a product of the small-school feel, though it’s likely due to the culture that the school has grown over the years.

The catchment area of the school is large, with students arriving each day from as far away as Kanata, Barrhaven, and Manotick. It’s a diverse student body in the ways you might expect, but in other ways as well, including financial, cultural, linguistic, and intellectual. There is a breadth of interest, and there isn’t a sense that Westboro is a primarily athletic school or focused more on a specific academic area. “We have a lot of quirky kids,” says Garrard, “and that’s kinda cool!” It is. “We have all these different sorts of kids that all have a place.” On a clear day, it’s common to see 20 or more of them spread out on the lawn reading at recess time. “I think of recess as an incredibly important time of the day. This is where they’re learning tolerance, respect, conflict resolution. All these things that are life skills.”

This is a school where social capital is gained in part through academic success, and where that tide raises all boats: kids are engaged with the material because they are surrounded by others who see the value and enjoyment in being engaged. Nevertheless, there’s a lot of play, interaction, and relationships, both within and across the grades. That includes mentoring relationships—the big brother, big sister style of mentorship—though less formal interactions are evident as well. The school yards are divided by age—there is a yard dedicated to K through Grade 3, one for Grades 4 to 8, and one for everyone—though students aren’t barred from entering any of them, no matter their age or grade level. The older kids are encouraged to play with the younger ones as often as they want, and they do. The soccer yard is technically within the K-3 play space, though most often there are children of all ages playing soccer there, the older ones helping the younger ones along a bit, but otherwise all just having a lot of fun together. During the winter months it’s not uncommon to see older kids pulling the smaller ones around on a sled, or giving piggy back rides, or just sitting on a bench chatting. Staff and students are divided into four houses. House events and identities contribute to relationships across the grade levels. Rewards for achievement are group oriented. The day before I visited, for example, the Green House earned a dress-down day, an opportunity to come to school in their civvies rather than their uniforms.

Athletics

Caitlin Cadeau has been at Westboro for 12 years and has been teaching physical education full time for the last five of those years. She has played in competitive hockey since she was four years old. “That has always been my love and my passion,” she says, though she has recently also discovered a passion for pickleball. For her, the goal of the athletics program is to provide a springboard to living a healthy, active life. “We’re not here to build the next NBA superstar,” she says. “I’m hoping that the kids find something that they are interested in and love the idea of being active in whatever way works best for them.” A key aspect of her job, she says, is to provide opportunities for students to try new things and find something that they love to do. “The whole idea is to enjoy and value being active.”

“That builds into our ethos,” says Garrard. “You know, what are people’s values, and what are we even here to do? That importance of supporting each other while they try new things and recognizing failure as part of success.”

There are competitive teams, though admission to those teams is non-competitive. “We don’t have tryouts; everyone participates,” says Garrard. There’s a no-cut policy, so if you want to be on the soccer team, you’re on the soccer team. That’s true within the co-curricular programs as well. If you want to be in the band, you’re in the band. “I can’t imagine cutting someone from a team when they’re seven and saying, ‘You’re not good enough,’ ” says Garrard. “How could you even have learned how to do it yet?”

Cadeau tries to address student interest as much as facilities and resources allow. As interest among the students dictates, she brings in athletes, trainers, and teachers to offer workshops. She’s even brought in people to do different types of dance or has taken students out to CrossFit classes. Beyond that, she rightly makes great use of the resources at hand, most notably the indoor gym and the stellar playing field next door. She keeps activities outside as much as possible, weather allowing.

The main areas of competition for Westboro are cross-county running, soccer, and basketball, and the school competes with local schools throughout the school year. There’s an annual cross-county run in the fall, with a majority of the students in Grades 3 through 8 taking part. There are soccer tournaments for the same grades, and basketball tournaments for Grades 5 through 8. In the spring there is track and field for Grades 3 through 8 as well as one for the primary grades. Everybody gets equal playing time within practices and competitions.

Phys-ed classes include a broad range of sports including floor hockey, badminton, ringette, and volleyball. The younger kids participate in dance, gymnastics, and co-operative games. Cadeau describes the student population as generally active, both in school and beyond. “They do a wide range of sports and recreational activities outside of school, and then bring those interests into the school,” she says. “I think we have a really nice cross section of skills and abilities that lend really well to each other.” There are some informal activities as well, such as the morning running club that kids can drop in on.

Wellness

“I really think the relationships, and building relationships, is the thing that’s going to take you to the next level,” says Rhodenizer. “And what that looks like is often in the small bits.” One of the “small bits” is simply being available, having multiple opportunities for informal contact at points throughout the day. “Teachers are busy, administrators are busy, and you need to schedule it.” So, he does. “You need to get up, move around, get into classes … make sure we’re out front talking to parents at the start of the day, checking in with kids.”

Rhodenizer sees relationships as key to the strength of the academic program as well as the wellness program and works to bring them forward. “If you’re building relationships, and kids start to feel more comfortable, then they’re able to do the enriched curriculum,” says Rhodenizer. “If you’re not comfortable and happy and enjoying where you’re at, all that stuff is for nought.” It’s hard not to be affected by that kind of thing. “Whenever we’re looking at kids, or adults for that matter, you’ve got to look at the whole piece.” Indeed, you do, and that he addresses that in such concrete ways adds strength to the entire offering.

Four years ago, Rhodenizer instigated an approach to academic and social wellness where during monthly professional development meetings teachers are given a set of cue cards, each one bearing the name of one of their students. Rhodenizer puts a line on the wall and asks them to place each child above or below the line depending on how they are forming relationships with others, or how well they’re interacting with others. “Do they have a lot of friends? Are they able to make connections? Are they unhappy? … Who needs a friend? Who needs help? Who’s succeeding?” It’s about academic success, ultimately, though it’s also about making sure that all the children have access to the supports and the people that will serve them best.

All is confidential of course, but the teachers then sign their names on the cue cards of students that are below the line, typically three or four students per teacher. Then, in the weeks and months ahead, they subtly take them under their wing. At recess, in the halls, they keep an eye out, perhaps touching base here and there. They monitor the relationships that each student is forming, maybe subtly helping some relationships develop. “All those things that we do differently than other schools,” says Garrard, “it goes back to size. We can do [those things] because we know all these kids and they all know each other.”

In larger schools the wellness program tends to have a sharper profile, including suites of offices dedicated to the guidance and counselling program. That can, and often does, look impressive, though it can also inadvertently hive off the wellness program as something separate from the daily life of the school. Here, the program of care may not be as obvious—there isn’t a guidance office, for one—but care is more integrated, and ultimately more attentive.

The teachers vocally appreciate the close relationship they have with parents of the school, knowing that they, too, share in the greater goals. “I think that makes the biggest impact, that you have somebody there that you know, that you’re connecting with, and you’re working together for your common goal.” I ask Nathalie Poirier, a Grade 7 and Grade 8 French and social studies teacher, why she feels that’s important. “Because I think the kids need to know that. That you’re working together as a support group. They feel safe and that you’re on the same page. That you’re there for them.” That’s a common theme when speaking with teachers here: the work of the school isn’t just the work of the classroom, but also in creating a community of support that extends beyond the walls of the school. “In the twenty years that I’ve been here, that’s been one of the biggest draws. That I know I have the support from the parents and vice versa,” says Poirier. That culture of engagement has been there from the start, as has an understanding in how important it is to the student experience. Says one teacher, “each child has a team that is rooting for them.”

Getting in

There is a waiting list in most grades, though the acceptance rate is quite high, both for the region and the country, with 90% of students who apply ultimately finding a place. There are all the admissions tools that you’d expect of a school of this size and stature, including interviews and provision of recent report cards. A visit to the school is strongly encouraged, though not required as part of the admission process. As well it should be. On that initial visit families meet with the director of admissions as well as student ambassadors. I met with them, too, and they’re as charming as they are down to earth. Across the board, staff and students are open and honest, willing to answer any question, and to follow up on anything that they may not have immediately to hand.

The school also requires assessment visits, where the student comes and spends anywhere from 2 hours to a full day in the classroom, depending on grade level. They participate in whatever the class happens to have going on that day, and the homeroom teacher will spend a bit of one-on-one time. The term “assessment” is meant in the broadest sense, in that it’s a chance for students to experience the environment, and for all parties to see if the fit is correct. In our experience, fit, as well, is meant in the broadest sense. This isn’t a school that intends only to enrol the highest fliers in terms of academics, but instead to enrol the students who need the school and who will mesh well with the culture it offers. The admissions process is aimed at finding mission-appropriate families, those that share the values and the intentions of the school. Offers of admission are made quickly, soon after the visit, and not at a set time, say the “offer day” in February which is the case at some private and independent schools. Parents and students both report that the entire admissions process feels comfortable, personal, and enjoyable.

Westboro is very reasonably priced, and in our rankings is not within the ten most costly schools within the Ottawa region. It’s a not-for-profit school, so tuition fees cover the operational costs of educating a student. It accepts donations and engages in some fundraising to help cover capital expenses though doesn’t rely on them. Fee schedules, per the parents I spoke with, are accurate and uncomplicated, with no unexpected costs arising at any point within the school year. There is a one-time annual consumables fee of $650 to cover incidentals and trips, rather than billing families for those things as they arise. Before- and after-school care for primary students is not included with tuition, but is very reasonably priced, and offered on an as-needed basis rather than a set fee for the year. There is an enrolment deposit of $1000, credited toward the first tuition instalment, which is also on par with other schools in the region. Sibling discounts are available, as are instalment plans. Tax receipts are issued for the full cost of tuition for JK and SK, and for 20% of tuition for Grades 1 through 8.

The takeaway

Westboro was established in 1993 by a group of parents who wanted a quality bilingual elementary education for their children. It began with a single Grade 1 class comprised of just six students. Needless to say, the school has grown, though—as at the beginning—growth has been an expression of need within the community. Further, the sense of community within the school is encouraged and prized. The focus remains centred on providing an authentic, effective bilingual program within a setting that addresses academic and social development. It is a place where students grow into a sense of themselves as learners and take part within a community. The ideal student is one able to thrive in a challenging, active educational environment. As such, at Westboro those who enrol will join a student body of true peers, one in which social currency is gained through achievement in all levels of student life. For many, that experience alone can be transformational.